Aca Nikolic

"The Professor”

RETROCOACHES

Antreas Tsemperlidis

7/15/20259 min read

Lefteris Subotic had just placed the phone back on its receiver, visibly troubled. The man he had spoken to moments earlier sounded weak and resigned to his fate.

“Professor, you’re strong, you will get through this too”

Subotic had told him, trying to encourage the exhausted patient lying in that Belgrade hospital.

“No, Slobo, I can feel it, the end is near”

Replied Aca Nikolic, who had realized he had little time left. Five days after that last conversation with Subotic, on March 12, 2000, the greatest coach in Yugoslav basketball history passed away, forever entering eternity.

The man who embodied the plans of the “Holy Quartet” within the four lines of the court was born in Sarajevo on October 28, 1924, into a wealthy family with roots in Brcko, a city on the border with Croatia. That day, his mother, Krista, had visited her sister in the Bosnian capital when she went into labor; her son was in a hurry to come into the world, being born premature at seven months. His father, Djordje, was 62 when he was born and adored him greatly; as a merchant and hotel owner, he could provide him with a life free of financial worry. His father’s growing business obligations made it necessary for the Nikolic family to move to Belgrade, where Aleksandar completed his education at “King Alexander I” Gymnasium in the Banovo Brdo neighborhood. In 1942, amid World War II and the Nazi occupation, Nikolic took the entry exams to study law, aiming for an academic career. During the same period, the first local basketball championship was organized in Belgrade. Perhaps this was where the four dreamers, young Yugoslavs of almost the same age, first met. What is certain is his friendship with Borislav Stankovic; they first played tennis together at Tasmajdan, and later basketball on the red clay of Kalemegdan. Together with Bora, in the small apartment on Kosovska Street, Aleksandar would share the food parcels his mother sent him from Brcko, singing along to the slow rhythms of traditional Bosnian sevdalinka songs.

When the war and occupation ended in 1945, the youth of the new homeland, rising from the rubble, yearned to play sports, to feel alive. Basketball became an outlet. New clubs were founded, including Red Star and Partizan. Nikolic, Stankovic, Saper, and Popovic initially joined Red Star’s roster, and five months after the war ended, they traveled to Subotica to challenge the Yugoslav Army team for what they thought would be the first national championship. Upon arrival, Nikolic was informed that he was still registered with the militia and was obligated to play for the opposing team. Unable to refuse, Aca played for the JNA team, scoring four decisive points that led to a 21-16 victory for the Army team. After the game, Colonel Ratko Vlahovic handed him the document releasing him from the Yugoslav militia. The four friends saw that basketball had potential; it matched their people’s spirit and had what it needed to evolve and become the national sport. Yet, it still required time and hard work, and they weren’t ready yet. This became evident in the first international tournament Yugoslavia participated in with them as players. In 1950, the Plavi traveled to Argentina to participate in the first World Championship. The Yugoslavs finished last, in 10th place, losing every game in Buenos Aires, and forfeiting their final match against Spain, refusing to play since the two countries had no diplomatic relations. Upon returning to Belgrade and after long discussions in the Kosovska apartment, they concluded that they could contribute to basketball not as players but as coaches and organizers. They waited patiently for three years, and in the summer of 1953, after the EuroBasket in Moscow and the retirement of Stankovic, who was the last of the quartet still playing, they presented their plan for developing the sport to the federation head, Danilo Klezovic. Klezovic proved perceptive and accepted the suggestions of these enthusiastic young men, including the proposal to appoint the 28-year-old Aleksandar Nikolic as the head coach of the national team.

Success did not come immediately; the road to the top was not paved with roses. By the end of the 1950s, Yugoslavia had only a sixth-place finish in the 1957 EuroBasket to show for its efforts, finishing at the bottom of the standings in the World Championship and not participating in the Melbourne Olympics. However, the pool of players eventually bore fruit, with talents like Daneu, Djerdja, and, of course, Korac emerging. The first medal for Yugoslav basketball, and the first vindication for Aca, came in 1961 in Belgrade when the Plavi reached the final of the EuroBasket, facing the mighty Soviet Union and its 2.20-meter “giant” Janis Krumins. Nikolic’s players couldn’t stop the Soviet star, losing 53-60, but the silver medal was a huge success and the first sign that the “Holy Quartet’s” system was effective. A silver and a bronze medal followed for the Yugoslavs in 1963 within five months, first at the World Championship in Brazil and then at the European Championship in Poland. Shortly after the EuroBasket ended, Nikolic, with complete freedom to act, traveled to the cradle of the sport, the United States, to study the American methods and bring new elements into the Yugoslav model. He spent six months in America, attending NBA and college games and practices daily, experiencing what he described as “a different kind of basketball.” This trip to the sport’s Mecca was pivotal in his career, completely changing his understanding of the game and sparking the creation of the “Nikolic school.” Upon returning to Yugoslavia, his first proposal concerned not coaching but infrastructure. In America, he saw how important game conditions were and insisted on building indoor courts so players would not be at the mercy of the weather. He remained the national team’s head coach until the 1965 EuroBasket before handing the reins to Ranko Zeravica, as Italian side Padova awaited him.

Padova, a modest team in the Italian league, was transformed under Aca with the addition of American Doug Moe, “the best player I ever had,” as Nikolic described him, finishing third behind Olimpia Milano and Varese with Moe as the top scorer. The following year was less successful, but they avoided relegation, and “The Professor” returned to Belgrade, although he had now caught the eye of major Italian clubs.

Wanting to stay close to his wife and two daughters, he remained in Yugoslavia for two years with OKK, and it was during this time in Belgrade that he received the tragic news of Korac’s death on June 2, 1969. The loss deeply affected Nikolic, as Radivoj was one of his favorite players and the cornerstone of the Plavi project. Stankovic, Saper, and Popovic urged him to take over the national team again ahead of the World Championship in Ljubljana, but Aca declined, supporting Zeravica instead.

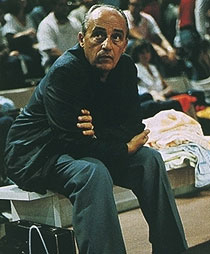

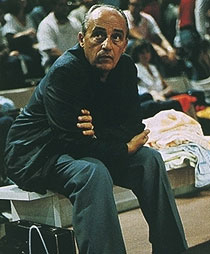

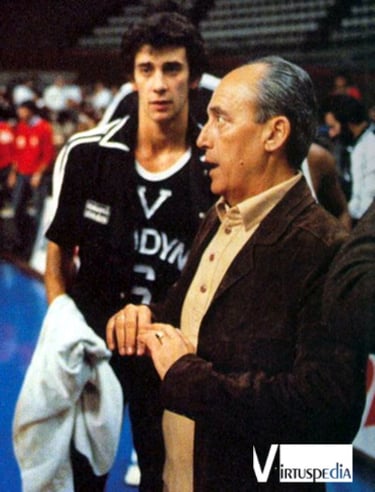

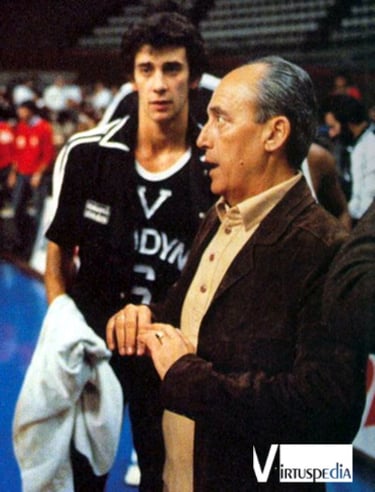

Around this time came an offer from Giovanni Borghi to coach Varese, as the Lombard patron saw in him the man who could deliver the European Champions Cup. Borghi asked, and, laconic as always, Nikolic replied, “It will be done.” The pack was ready to hunt, needing a leader, and they found him in this small-statured professor with the clever eyes who would show tactics once on the blackboard before erasing them, who valued physical fitness greatly yet was a true teacher of tactics, a man who respected and loved his players, believing that “the art of basketball was invented by players, not coaches” and that “a coach must learn from his players.”

With complete trust in his players and inspiring them, Nikolic laid the foundation for the Italian dynasty in the Champions Cup, bringing the prestigious trophy to Lombardy three times (1970, ’72, and ’73) and winning eleven titles overall. He instilled a winning spirit in Meneghin, Ossola, Raga, and Morse, fulfilling his promise to Borghi.

Thus, he accepted Red Star’s offer in the summer of 1973, deemed the ideal person to restore order in the Crveno-Beli locker room, which was plagued by conflicts between Slavnic’s “clique” on one side and Simonovic’s on the other. Neither dared provoke Nikolic’s wrath, and Red Star became a model team in the 1973-74 season, ending it as European Cup Winners.

For the next two years, Aca worked in the familiar Italian league with Fortitudo Bologna, experiencing both sides of the coin: a painful relegation to the newly formed A2 division in the first year, followed by promotion back to A1 the next season.

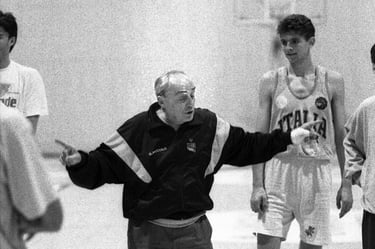

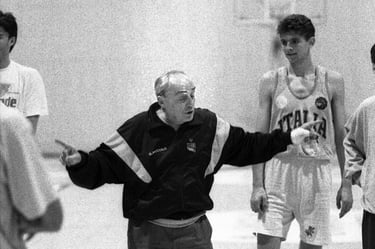

Now 52, with nearly 25 years on the bench, “The Professor” could have retired if he wished, but he still lacked a gold medal in a major tournament with the national team. The Plavi, boasting the best generation of players in their history, had entered their “Golden Decade,” and Nikolic seized the opportunity to enrich his collection with a EuroBasket gold in 1977 and a world title the following year in the Philippines, taking revenge on the Soviets for the defeats of the 1960s.

Having won nearly everything at both national and club levels, he handed over the national team keys to his former player Petar Skansi and, to everyone’s surprise, moved to Cacak to coach Borac. The team had produced great players in the past, like Kicanovic and Radmilo Misovic, but was considered too small for a coach of Nikolic’s stature. Yet “The Professor” worked as he knew best, managing to lead Borac to qualify for the Korac Cup, trusting young players like 17-year-old Goran Grbovic and a cerebral point guard named Zeljko Obradovic, demonstrating his firm belief in his own maxim: “The young player must be on the court at the end of a close game, even if he makes a mistake, and not when you’re leading by 20 points.”

Aca continued to be active on the sidelines until 1985, coaching four Italian teams, starting with Virtus Bologna, followed by stints at Venezia and Pesaro, and finishing at Udine. Afterward, he stepped away from the bench but did not leave basketball. He remained active behind the scenes, now serving as a mentor whose footsteps young coaches would follow, turning to him for advice.

This is exactly what the management of Jugoplastika did in the summer of 1986 when they asked him to take over the young team in Split after Slavnic’s departure. Nikolic declined, but in his typically pessimistic tone, he suggested an assistant from Crvena Zvezda, telling them: “I have the right man for you, but I don’t know if you have the courage to give him the position. He’s very young, 34 years old.” The leaders of the Žuti did not think twice and rushed to sign Aca’s chosen one, bringing Bozidar Maljkovic to Split, and what followed is simply history.

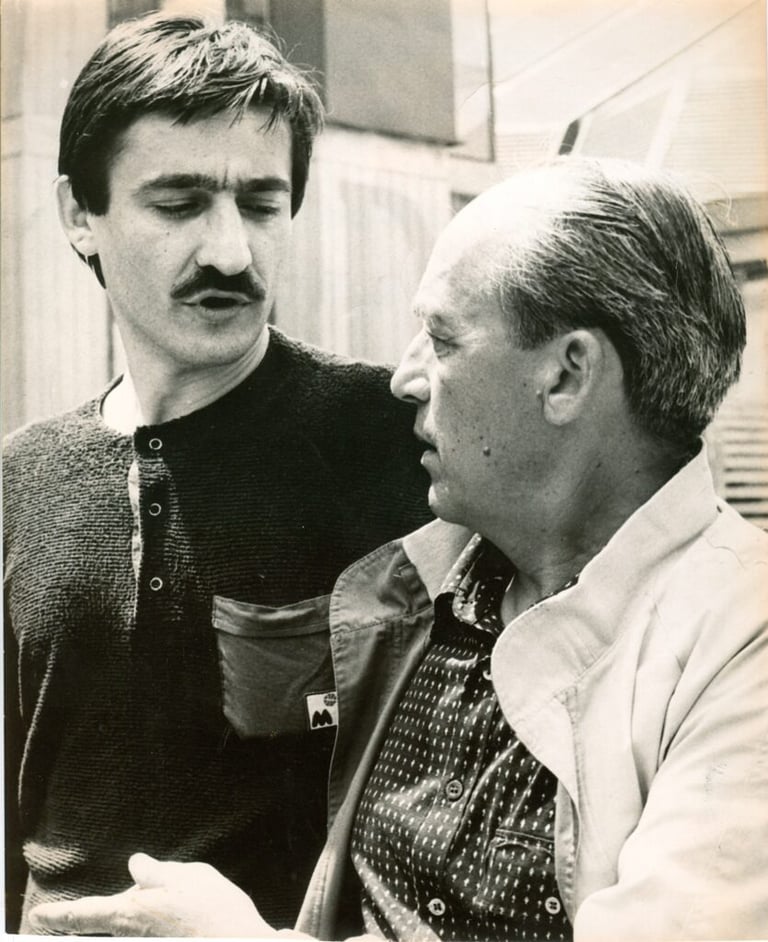

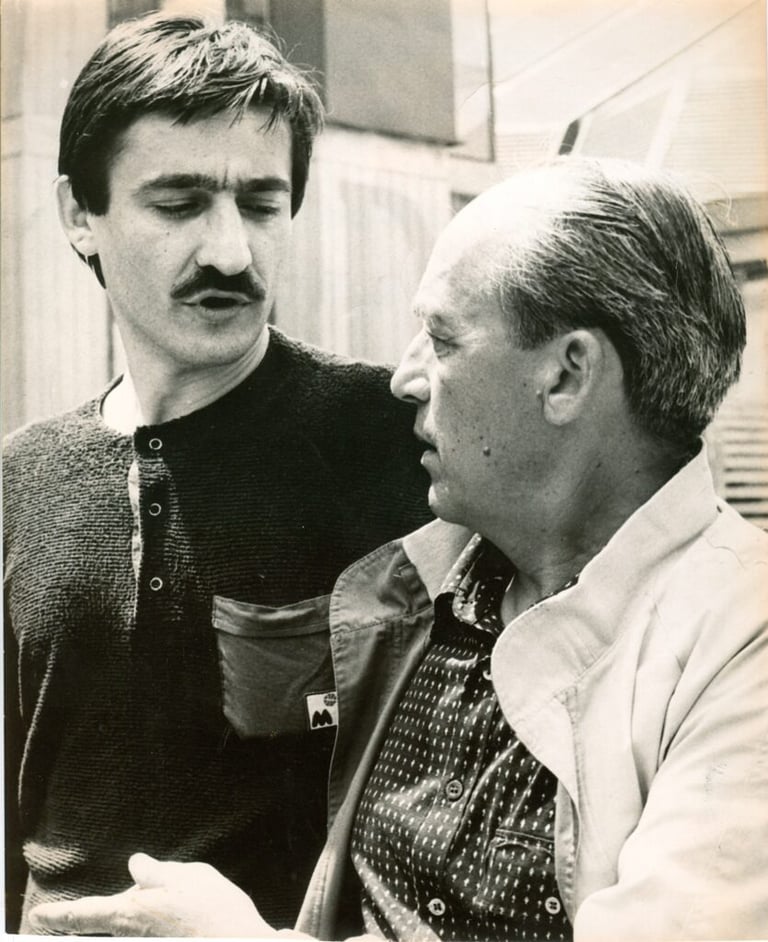

The next to knock on Nikolic’s door was a young coach from Partizan who, during a tournament in 1984 where his team was participating, found the “Professor” watching the game, and a conversation between them completely changed the way he viewed the game.

Zeljko Obradovic had played 38 minutes in the game but had only scored two points, sitting disappointed with his performance on the bench when Nikolic approached him, and to his surprise, congratulated him, saying: “You were the best player on the team; your organization was exemplary.” Zoc never forgot those words, and in June 1991, he called Nikolic, who responded immediately, eager to share his knowledge. The young players of Partizan listened to his advice with awe during practices, and during the “Miracle of the Bosphorus,” Danilovic and Djordjevic climbed into the stands of the Abdi Ipekci Arena to embrace him, acknowledging his contribution to their achievement.

The “Professor” never refused anyone who sought his advice and guidance. This is how, in the summer of ’92, he found himself at Aris, serving as a technical advisor to Steve Giatzoglou. His tenure with the “Emperor” was brief, as he faced criticism from journalists who considered his ideas outdated and believed that the sport had passed him by. However, Roy Tarpley did not share this view, and until his death, he spoke with respect about Nikolic’s methods and work ethic.

Fate brought him back to Thessaloniki two years later when another of his beloved “children” from the national team years—even though he had cut him from the 1978 team roster—Slobodan Subotic, who had taken over Iraklis, sought his guidance to navigate the deep waters of coaching. Slobo, who always speaks of the “Professor” with immense respect and love, often recalls how much Nikolic helped during Iraklis’ excellent 1994-95 season in the Greek league and Europe, and how deeply Aca influenced his coaching philosophy in general.

Until the end of his life, he never stopped talking about basketball, drawing plays even on pizzeria napkins at 3 a.m., watching his students triumph, and receiving worldwide recognition with his induction into the Hall of Fame in 1998.

The self-taught coach, the man with the unique gift of seeing ahead of his time, now rests in the Alley of Distinguished Citizens in Belgrade. Bozidar Maljkovic’s words during his farewell speech offer a glimpse into the legacy Aca Nikolic left on Yugoslav and European basketball:

“He had a tremendous passion for the game. Many of us were his students, and the first thing he taught us was how to become better people. He generously shared his immense knowledge with us, and we all owe him a great deal.”

This was the “Professor.”