Alexander Sizonenko

“The sad life of the Soviet Gulliver”

RETROPLAYERS

Antreas Tsemperlidis

12/23/20259 min read

Janis Krūmiņš, Uvais Akhtayev, Tkachenko and Sabonis are the four names that the former Soviet Union presented in the sport of giants, and their height characteristics (all 2.20 meters and above) placed them in the category of “giants.” Paradoxically, the one who surpassed them all in height never wore the jersey with the hammer and sickle, and today very few people know the name Alexander Sizonenko—mainly as the tallest basketball player in history. He never became a star of the sport and never crossed the threshold of the USSR national team. Yet he lived a life worth remembering.

He was invited to a television show dedicated to the most unusual people and appeared in a feature film. He was offered a large sum of money for his body after his death. He was listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the tallest man in the Soviet Union. At the time his record was registered, he stood 2 meters and 39 centimeters tall, and toward the end of his life he reached 2 meters and 45 centimeters. That is, although he was 30 centimeters shorter than Robert Wadlow—the tallest man in history, who died at the age of 22—Sizonenko lived thirty years longer. Yet during that life, fate showed him its cruel face…

Sizonenko’s hometown was the Ukrainian city of Zaporizhzhia in the Kherson region, a place immortalized forever in 1880 by the painter Ilya Repin in his magnificent work titled “Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed IV.” On March 21, 1959, the protagonist of our story was born into an ordinary family: his father was a machine operator at the local factory and his mother a housewife. Family life in the Soviet Union went smoothly for the Sizonenko family until the day they realized that their son was growing at an excessive rate, unlike his older brother, who had normal height and build. At the age of 10, Alexander already saw the world from 1 meter and 70 centimeters. But it was only when he reached 14 years of age and a height of 2.02 meters that his parents became alarmed and turned to doctors, who diagnosed him with acromegaly—a rare but very serious hormonal disorder of the pituitary gland that causes excessive growth of the extremities. He underwent two surgical operations without significant success. The medical prognosis for Alexander’s life expectancy contained no optimism at all: he was expected to die before reaching the age of 35. But as in the similar case of Uvais Akhtayev, sport appeared as a lifeline, and his involvement with basketball began entirely by chance.

After completing his schooling, he began learning the trade of an electrician; an athletic career was not even a possible prospect in the picture of his life.

The decisive moment of Sizonenko’s entry into sports came in 1976, when he had to go on an errand to the city of Novaya Kakhovka. On his return, he found himself on the same bus as the basketball team of Spartak Nikolaev. The team’s coach, after recovering from the shock of seeing a 17-year-old who already exceeded 2.17 meters in height, approached him hesitantly, spoke to him, and invited him to try his luck in basketball. Alexander initially refused the proposal; until that moment he did not even know what shape a basketball had, and his shy nature held him back from taking such a big step. However, word of the existence of a man with his physical attributes soon reached the ears of one of the many “scouts” searching for new blood on behalf of Vladimir Kondrashin, the coach of Spartak Leningrad and Olympic gold medalist in Munich in 1972.

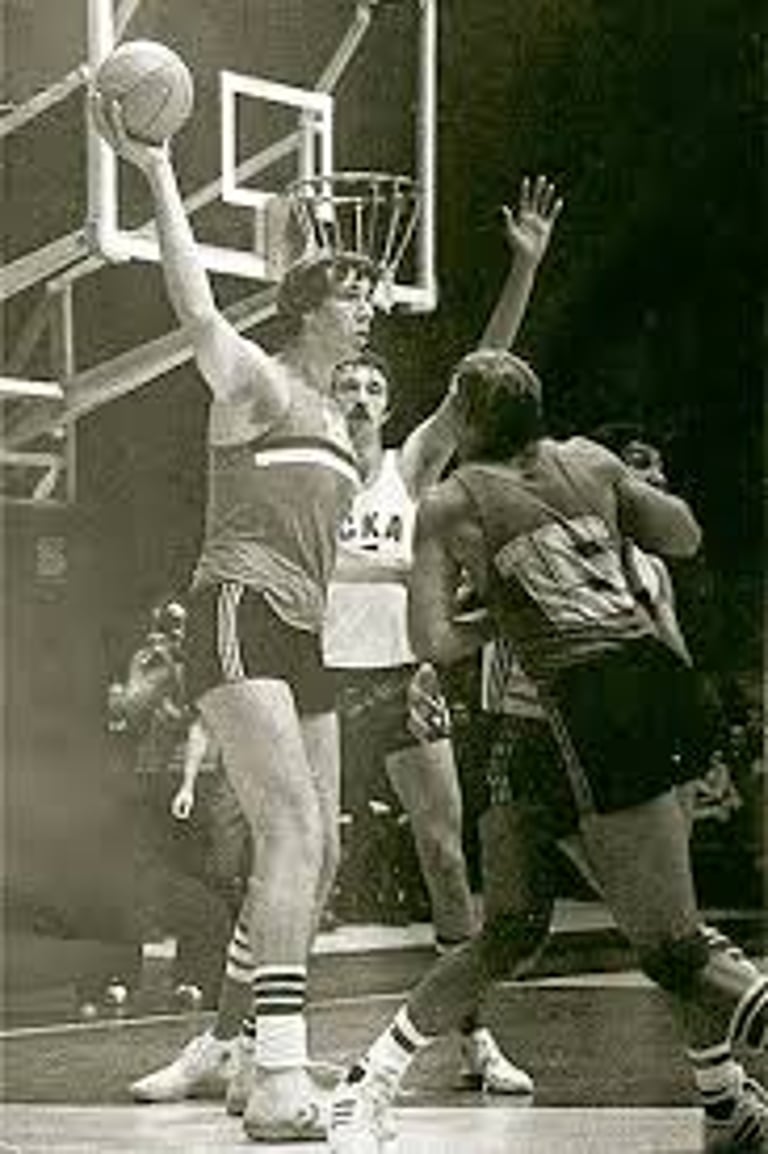

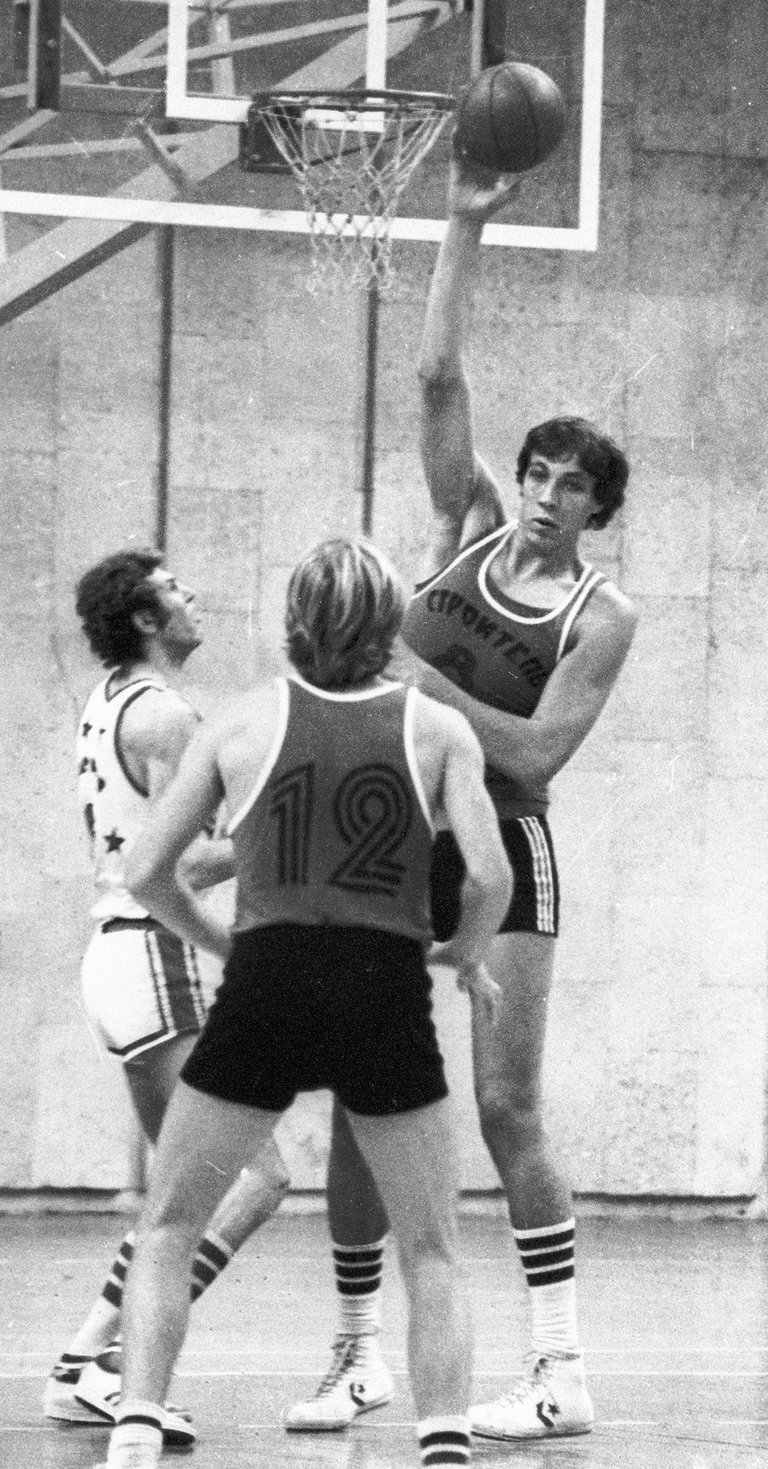

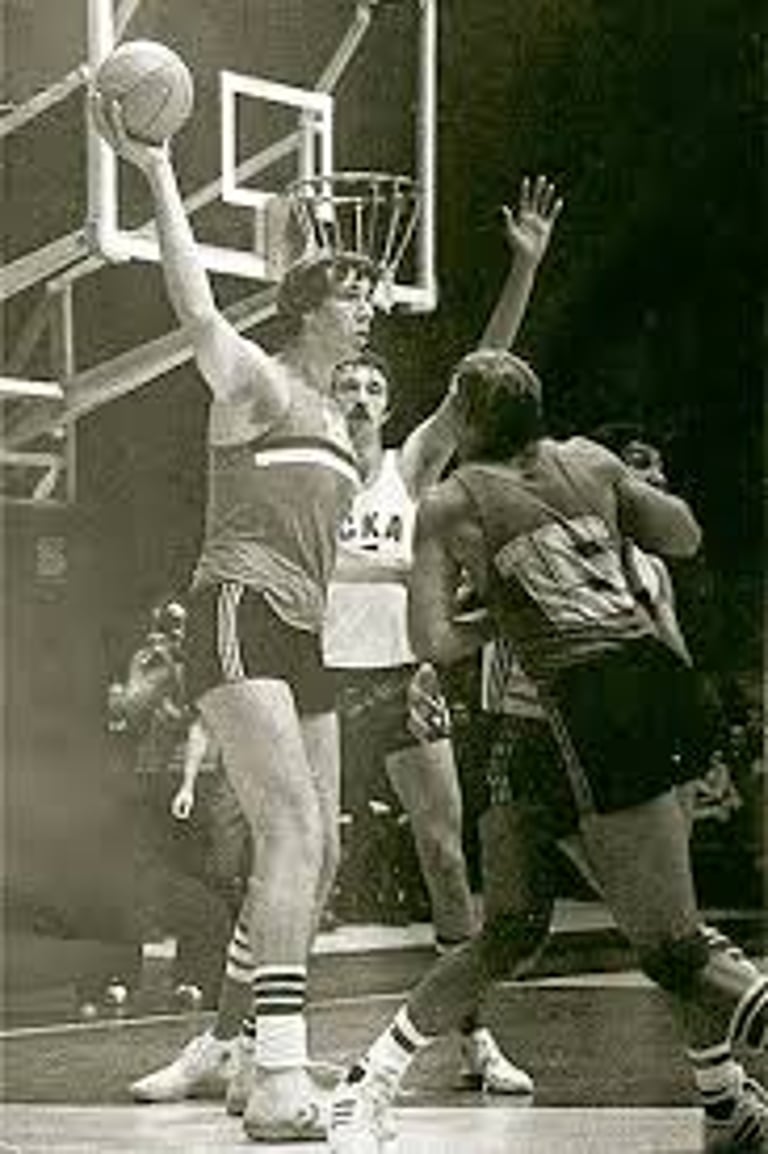

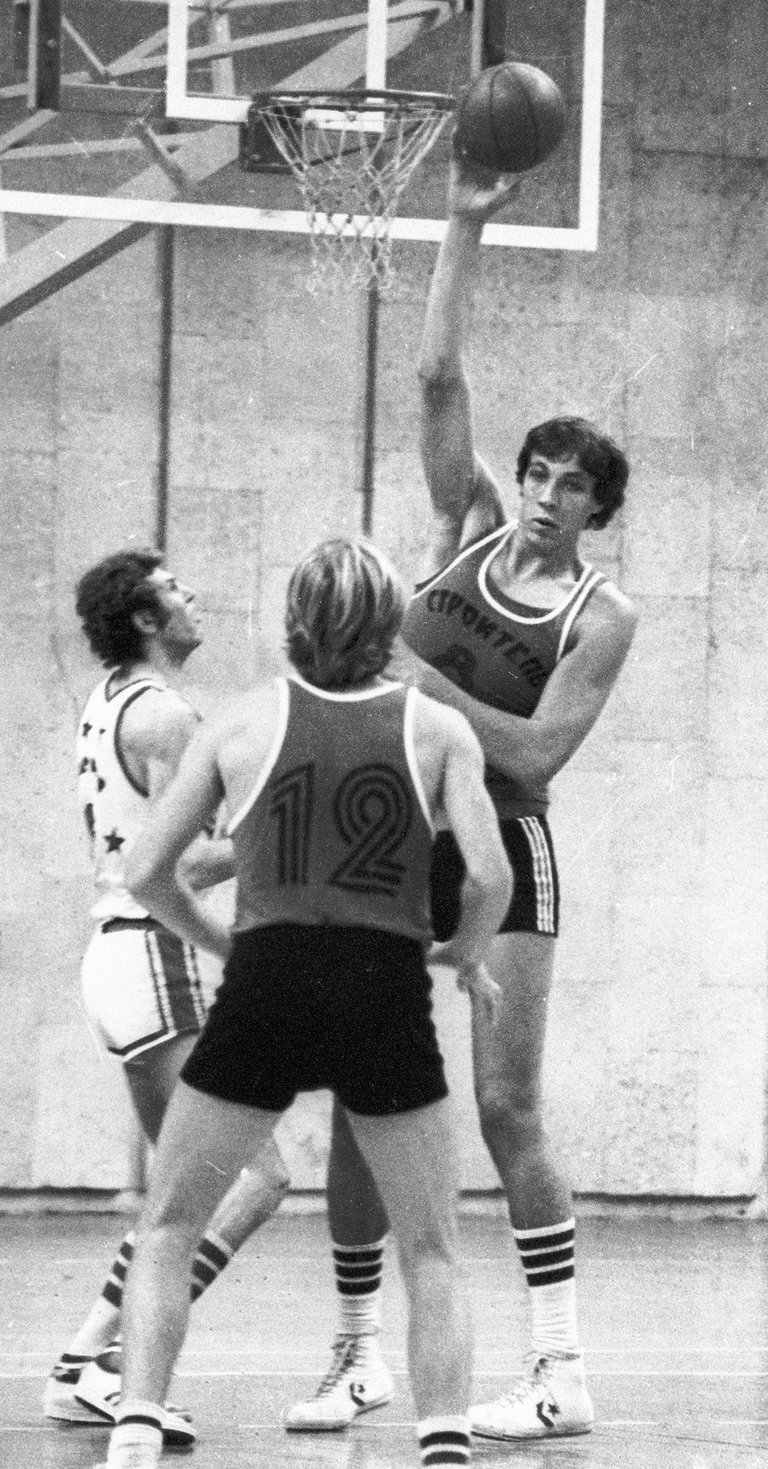

This time Sizonenko was convinced, and without having played a single game in Ukraine, he found himself with another Spartak—this one from Leningrad, the great rival of CSKA Moscow in the 1970s—and under Kondrashin’s guidance. In Leningrad, Sizonenko came under the protection of the hero of Munich, Alexander Belov, and the young giant quickly showed that although raw, there was something in his case that, with hard work, could be developed. In his first training session he impressed everyone by making 19 consecutive shots, leaving his teammates speechless, as at that time it was uncommon to encounter such tall players with a good mid-range shot. The future looked promising—but things did not unfold exactly that way. From 1976 to 1978 he played for Spartak, where he quickly established himself in the first team. Alongside Kondrashin, he achieved second place in the Soviet championship, but he was unable to hold onto his place on the team for long. Kondrashin, always an innovator, was then promoting a faster style of play for Spartak—a speed that Sizonenko could not adapt to. With his height he was excellent at rebounding and a good defender, but the truth is that Kondrashin always trusted Silantyev more as Belov’s substitute. Sizonenko could have remained at Spartak by accepting a complementary role, had it not been for the tragic incident that marked the end of his stay in Leningrad. In October 1978, at the age of 26, Alexander Belov died of cardiovascular sarcoma. The tragedy led to stricter medical checks for athletes with known health problems, and Sizonenko was one of them. With Belov’s death, he not only lost his best friend and mentor on the team, but due to his own condition, Spartak released him. Kondrashin advised him to move to a provincial team, where it would be easier for him to go unnoticed and continue playing. Following his coach’s advice, Sizonenko moved to the city of Kuibyshev, today’s Samara.

At the same time, the local basketball team was taken over by Genrikh Primakov, a coach with a good reputation in women’s basketball. Primakov was ambitious and a man with big plans; the first thing he did was persuade the management to rename the team Stroitel Kuibyshev and set the goal of promotion to the top division of the USSR championship. He was looking for new players, and his friend, referee Oleg Gorbatov—who had officiated games in which Sizonenko played—advised him to sign him. And so it happened: Alexander, at the age of 20, found himself on the banks of the Volga. In Primakov’s “quiver,” Sizonenko was the most valuable arrow. With his contribution, Stroitel entered the elite of Soviet basketball within two years. Tkachenko, Belostenny, Sabonis, Deryugin—all the great Soviet centers faced him at times and struggled greatly. When Tkachenko was still playing in Ukraine for Stroitel Kyiv, accustomed to dominating everyone, he came up against Sizonenko. He scored only two points…

In a friendly match against Žalgiris in Kaunas shortly after Brezhnev’s death, Sizonenko scored 42 points against Sabonis. Arvydas looked small next to the 2.39-meter giant…

So why was this player never called up by Gomelsky to join the national team and be presented on the international stage? There is a widespread legend claiming that in those years the “Colonel” called him up for friendly matches against Puerto Rico as part of the preparation for the 1982 World Championship, and that Sizonenko was supposedly excluded due to visa problems. However, when this question was put to Vladimir Gomelsky, the son of the “Colonel,” his answer left no room for doubt: “My father never planned to include Sizonenko in a national team squad. His health condition was known to all coaches in the USSR, and of course Gomelsky knew it better than anyone.” Alexander continued to play in the domestic championship with Stroitel, but after 1983 painful injuries to his legs began, forcing him to miss games and training for long periods. And the worst? In 1985 Primakov died, and his replacement on the Stroitel bench made it clear to Sizonenko that he was not counting on him. Combined with the injuries, Alexander decided to retire in 1986, at just 27 years old.

Perhaps in another country he would have been granted a lifelong pension to live the rest of his life with dignity. But not in the Soviet Union during the era of “Perestroika.” The authorities judged otherwise and granted him a meager pension of 63 rubles, while the average pension in the USSR was 100 rubles. The money was insufficient, and he barely survived. During his career in a system that hid behind amateurism and collectivism, Alexander failed to save any capital. After it ended, no one cared for him—everyone forgot him. Despite holding two degrees (one from a technical vocational school as an electrician and another from the Kuibyshev Institute of Economics), he could not find a job. Only the generosity of compassionate neighbors kept Sizonenko alive. His friend Sergei Volkov spoke to the newspaper Samarskiye Izvestia about his visits to Alexander’s home. At first, Alexander would proudly refuse his neighbor’s help, until one day he admitted with tears in his eyes: “I don’t have enough money for food.” Volkov took the initiative, and in 1987 published an article in the magazine Sobesednik describing the miserable living conditions of his friend, which shocked the entire Soviet Union. With the intervention of Kondrashin and Gomelsky, his pension was doubled, and a tailor made new clothes to his measurements. A film was even made starring Sizonenko himself, titled “It’s Hard to Be Gulliver,” and it was shown in cinemas like a fairy tale with a happy ending. A student from Leningrad, Svetlana Gumenyuk, rushed to Kuibyshev ready to help Sizonenko. Shortly afterward, Alexander and Svetlana got married.

In 1992, after the fall of Communism in the former Soviet Union, Sizonenko received a series of offers from various television shows, mainly from Eastern Bloc countries. In Czechoslovakia, the film studio Barrandov Film invited him to play the role of the giant in “The Brave Little Tailor.” The famous German doctor Günther von Hagens invited him to Germany under the pretext of medical treatment, but in reality it turned out that von Hagens did not need him alive. He wanted to keep his body after his death to exhibit it in his notorious museum. He offered him a lifelong pension of 400 German marks per month in exchange for his body. Despite his poverty, Sizonenko—a man of deep religious faith—categorically refused even the increased offer of a lump sum of 40,000 marks, saying: “I am a religious person. I want to be buried like everyone else. They will not parade me around like a scarecrow.” Financial problems persisted during his marriage as well; money was never enough, and Svetlana ended up in court after being arrested for fraud involving forged checks. She was sentenced to two years in prison with a three-year suspended sentence. Shortly afterward, the Sizonenko family returned to Leningrad, which had regained its original name—Saint Petersburg. For a short time, Sizonenko lived with his wife’s parents in the village of Gorelovo, in a house without hot water or heating. His father-in-law opposed the arrangement and repeatedly put Sizonenko’s belongings outside the door, trying to force him to leave. Eventually, Alexander was forced to rent an apartment in a poor neighborhood. Once again, the money was insufficient, and many times—even though the rent was low—they delayed payment, hoping for the landlords’ understanding.

This was the turning point in a family life that was collapsing. Two years after the birth of their son, Svetlana divorced Sizonenko. He was left alone, and salvation came from the Sports Committee of Saint Petersburg and the personal support of three-time Olympic champion Tatyana Kazankina. They ensured that Alexander was housed in a municipal communal apartment. The problem was that the ceilings were extremely low—a house built in 1882, at the corner of Vostaniya and Ulyana Gromova streets. Health problems began to overwhelm him. He could now move only with the support of a cane at first, later with crutches. In 2007 he appeared at a basketball tournament in Saint Petersburg and met former teammates from Stroitel. For the press, this was a shock. How was it possible that Sizonenko was still alive? Doctors had predicted he would die young. Against all odds, he continued to fight. But his appearance that day was truly horrifying.

His face was disfigured, he was hunched over, dressed in rags instead of clothes, and on his feet he wore a pair of torn athletic shoes. Yet he looked so happy to see his old friends from Samara. A new wave of publications swept Russia. The old Spartak Leningrad still existed as a club, and its leaders mobilized charitable foundations to help. But the help came too late. In 2010 he broke his hip and was bedridden from then on. Spartak sent him to a rehabilitation center, but he soon returned home at his own request, waiting for the death that Sizonenko felt was approaching. In his final days he was irritable and short-tempered. His former Spartak teammate Mikhail Silantyev recalls that when he called him to say he would be a little late bringing some medicine, he heard an angry reply: “There’s no need to come. I will die here alone. I don’t need anyone.” On New Year’s Eve of 2012, Sizonenko could no longer move at all; his body had exhausted all its reserves. The next day he fell into a coma. He died in his sleep on January 5, in the same way he had lived—quietly, without disturbing anyone. Beside him was only his sixteen-year-old son, Sasha.

The money for his funeral was collected through donations—whatever each person could give. A coffin of his size cost 120,000 rubles. His friends had only 80,000. “Please, show compassion. This is all we have—take it and let us bury our friend,” they pleaded at the funeral office. “That is your problem,” was the answer they received. In the end, the remaining 40,000 rubles were found, and Alexander Sizonenko was buried at the Saint Petersburg Cemetery, not far from where Vladimir Kondrashin, Alexander Belov, and other members of Spartak rest forever.

Only a few people attended the final farewell, perhaps to confirm the words of Sizonenko’s favorite writer, Anton Chekhov, who once wrote:

“As I shall be alone in my grave, so I lived—essentially alone.”