Bobby Knight

"The General”

RETROCOACHES

Antreas Tsemperlidis

2/1/20265 min read

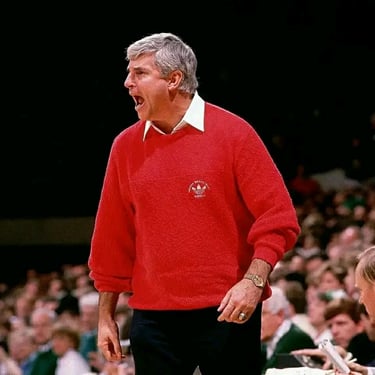

An explosive character, hot-tempered, misogynistic, a controversial personality but a truly great coach.

In the face of Bobby Knight, who was October the 25th in 1940 in Massillon, Ohio, all of the above traits were constantly expressed throughout his five decades of service as the “General” on the benches of college basketball, and especially that of Indiana University. In his very first game as a coach, at a high school somewhere in Ohio in the 1960s, he smashed the tactics board in anger. This was his maiden—but by no means his only—outburst, as objects and people around him would often become recipients of his rage. A lover of discipline, during his time as head coach of the United States Military Academy (our well-known West Point), at just 24 years old, and with future Indiana assistant Mike Krzyzewski as one of his players, Knight earned the nickname “Bobby T” because of the sheer number of technical fouls he received. Beyond technical fouls, however, Knight also collected wins during the six years he spent in New York, attracting the attention of one of the top NCAA programs—Indiana—which hired Bobby as head coach in 1971.

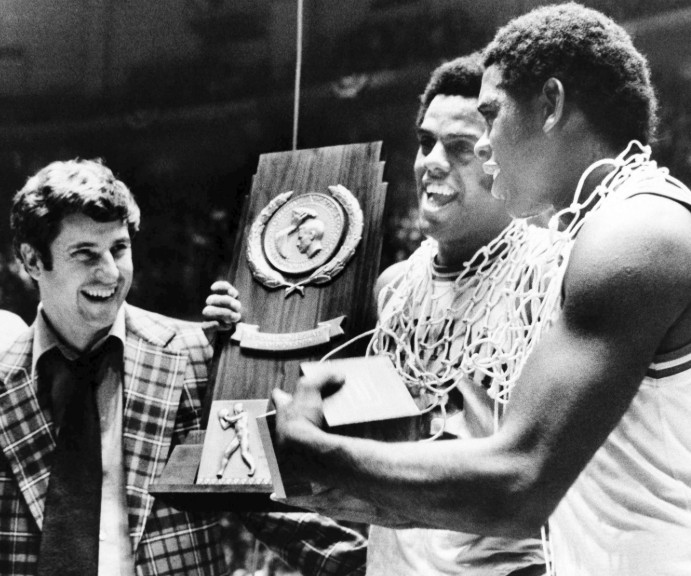

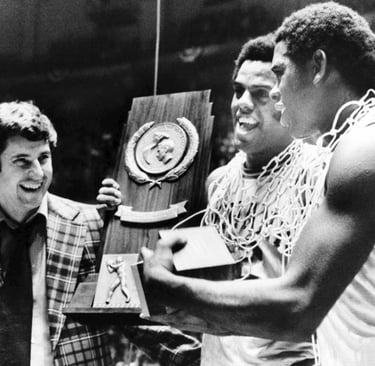

In a state where basketball is revered almost like a religion, Bobby Knight made enormous history, winning three NCAA championships, reaching the Final Four five times, claiming victory in 902 games, and to this day remaining the last coach to complete an undefeated season (32–0 in 1975/76).

With his famous “motion offense,” designed to create the best possible conditions for open shots, and with relentless full-court pressure defense, the “General” and his ever-changing lineup of “soldier” players established the university as one of the best in the country. The results proved that Knight’s methods were effective, and he made no concessions to anyone who could not tolerate the “torture”—both physical through exhausting practices and psychological.

Even Larry Bird himself lasted only one month before quitting and returning to French Lick, preferring to work for the local sanitation department rather than face Bobby’s bulging eyes and hear his constant verbal abuse. Michael Jordan, meanwhile, never forgot breaking down in tears in the locker room at halftime of the quarterfinal against West Germany in the 1984 Olympic tournament, when Knight forced him to apologize to his teammates for his poor performance. Years later, Bobby admitted that he did it to give Michael extra motivation, which ultimately led the Americans to the Olympic gold medal—he knew Jordan was the greatest basketball player he had ever coached. Knight demanded perfection from his players. That was his goal, and he believed the correct way to achieve it was through absolute control over everything. Athletes had to become part of his system. There was no democracy on his teams—only dictatorship, with himself in the role of the “tyrant.” His words during a 1985 speech perfectly captured his philosophy:

“Remember this, boys—there’s only one person beating the drum around here, and that’s me.”

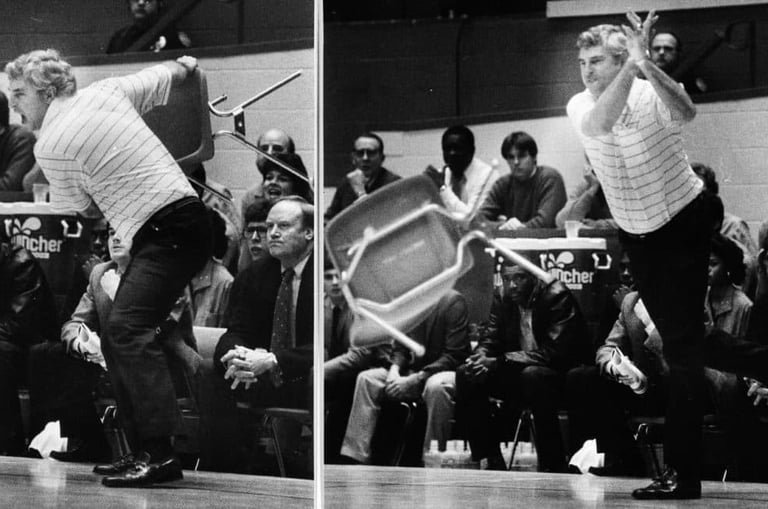

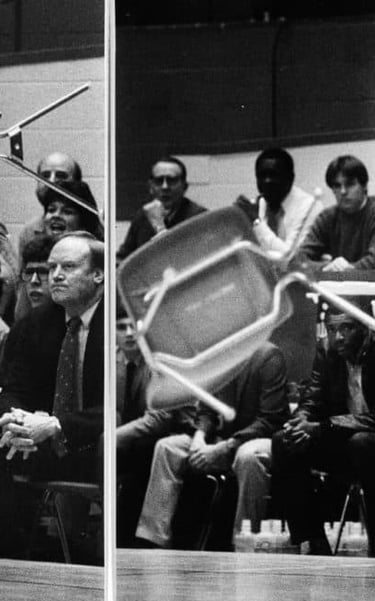

Whenever things on the court strayed from his plan, his reactions were extreme: throwing chairs onto the court, headbutting or grabbing players by the throat, kicking one of them after a mistake during a game. That player was his own son.

“My players tolerate me because they know that when I do something that may seem awful, I do it because I want to help them become the best they can be, at any cost. And I’m selfish enough to believe that I know better than anyone—professors, girlfriends, roommates—what they really need.”

This shows how Knight viewed himself: as someone entitled to intervene in every aspect of the lives of the young men under his command. His strictness had a purpose, and in that respect he was absolutely successful—the Indiana program was never involved in point-shaving scandals or under-the-table recruiting, and 96% of Bobby Knight’s student-athletes completed their four-year studies and earned their degrees.

“There’s no reason for me to change my habits”

That is what he said in an interview in March 2000. Just days later, however, video footage surfaced showing his violent behavior toward Neil Reed, the player he had grabbed by the throat during practice three years earlier.

He was summoned by the university administration, which made it clear that no tolerance would be shown for similar incidents in the future. Knight knew his days at Indiana were numbered. Worse than the threat of dismissal was the fact that the sanctity of practice had been violated. He passionately insisted:

“I love basketball as a game!!! The game. I don’t need 18,000 people screaming and all the rest. For me, the most enjoyable and sacred part of basketball is practice and preparation.”

In September of that same year, while walking toward the gym for morning practice, a freshman student shouted at him without a trace of shame: “Hey, what’s up, Knight?” and then burst out laughing with his friends. You can imagine what followed. The 60-year-old Bobby Knight turned toward the young man and grabbed him by the arm—some claimed he put him in a headlock—and began hurling every insult he knew at him. Amid the stream of profanity, one word kept repeating: “respect.” Two days later, for “unacceptable behavior,” Bobby Knight was fired from the position he had held for twenty-nine consecutive years. For some, he was an eternal hero; for others, a repulsive figure due to his excesses. The “General,” stripped of his rank, left Bloomington and vowed never to return.

He stayed away from coaching for a year, and in 2001 he went to Texas Tech University. There, he broke Dean Smith’s record for most wins, reached the NCAA tournament round of 64 four times with the Red Raiders, and in February 2008 he resigned, handing the team over to his son, Pat Knight—the same son he had once kicked.

After forty-six years in active coaching, he could finally enjoy retirement, but the bitterness over his dismissal from Indiana never left him. This was evident in 2016, when he did not attend the celebration marking forty years since the 1976 championship, stating that he would return to Bloomington only when everyone who had signed his termination papers was dead.He kept his word (the last of those involved died in 2019), and so in 2020, at the 40th anniversary of the 1980 championship, he once again stepped onto the Indiana court alongside Isiah Thomas and the rest of the Hoosiers, receiving a thunderous ovation from the crowd.

When his former player Mike Woodson took over as head coach in 2021, the “General” frequently attended games and practices, watching without intervening.

During the final two years of his life, as travel became increasingly difficult, the university provided him with a home near Assembly Hall—the site of his greatest triumphs. That same place, on the day of his death, November 1, 2023, was filled with people who wanted to say their own thank-you to the winner, the “General,” Bobby Knight.