Bosna Sarajevo

"Pure romance"

RETROTEAMS

Antreas Tsemperlidis

7/1/20256 min read

In Yugoslav basketball, there are beautiful stories of great teams and players, like Jugoplastika during the era of Kukoč and Rađa, and earlier with Šolman and Skansi, Partizan with Dalipagić and Kićanović, or Cibona with Dražen.

But none of these touched the heart more, stirred such emotion and tears, than the romantic saga of Bosna Sarajevo.

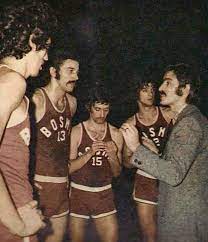

Two men are inextricably linked with the team and also with each other through a powerful bond. The first is the coach, the visionary and creator, Bogdan Tanjević. The second? The artist of the court, the dancer, the graceful sprite named Mirza Delibašić. In 1971, the 24-year-old Tanjević had just left OKK Belgrade and was preparing to join the roster of KK Oriolik, a team based in Slavonski Brod, a city divided by the Sava River—its northern part in Croatia and southern in Bosnia. While waiting for the championship to start and not having yet signed an official contract with Oriolik, Bogdan took advantage of the summer break and traveled to Sarajevo to observe Bosna's preparations—at the time playing in the second division.

It took only a few days before the club’s management, with the consent of coach Milenko Kovačević, offered the young man—who was spending day and night in the stands jotting notes in his notebook—the head coaching position. Tanjević, already seeing himself moving from the court to the sidelines, accepted, unaware of how far his creation would go in the years to come.

Without wasting time, "Boša" rolled up his sleeves and started building around his first signing, 22-year-old Svetislav Pešić from Partizan. At the same time, he promoted 19-year-old Žarko Varajić, and along with veterans Pavlić, Jelović, Nadaždin, and newcomer Bruno Soče, Tanjević led Bosna on April 28, 1972, before 7,000 fans at the Skenderija arena, to a playoff match for promotion to the first division against Zeljeznicar, who were tied with them in the regular season.

In the very place where, just two weeks earlier, one of the most iconic films in Yugoslav cinema history had premiered—"Valter brani Sarajevo" (Walter Defends Sarajevo)—Bosna’s players defeated their opponents 65–59. After 21 years, the team founded near the University of Sarajevo by Dr. Neđad Behlilović and a few of his students would participate in the top league for the first time.

Bogdan knew that if he wanted to compete for something greater in the toughest league in Europe at the time—the Yugoslav one—he needed immediate reinforcements. He sought something different, something Yugoslav basketball had never seen. He needed the unpredictable, the simple yet magical, the sixth sense. He needed the best 18-year-old in the country—he absolutely had to bring Mirza Delibašić to Sarajevo.

He traveled to Tuzla, the birthplace of "Kinđe", to talk with Mirza’s parents, Izet and Zajkana Delibašić, and with Mirza himself, to persuade them not to let him go to Belgrade and Partizan—who were dreaming of pairing him with Kićanović—but to stay in Bosnia so they could together challenge the Serbian and Croatian teams dominating the championship.

Delibašić was convinced by Tanjević’s passionate vision and became the most potent weapon in his arsenal. Starting in the 1972–73 season, that weapon would be launched with the ultimate goal: the Holy Grail of European basketball—a trophy no Balkan, let alone Yugoslav, team had ever won.

Bosna’s presence in the 1979 European Cup final was no accident but the result of hard work and the individual talent of its players. The team climbed step by step, strengthened by Radovanović in 1974 and Benacek in 1975. Even the absence of Tanjević in the 1975–76 season—due to his military service—and his replacement by Luka Stančić didn’t slow their progress; they were already a well-oiled machine, running on autopilot.

The first glimpse of the new Yugoslav basketball powerhouse came in 1977, when Bosna reached the league final. They tied with Jugoplastika at the top, and in a déjà vu of 1972, the title was decided in a single game. This time, however, it ended in heartbreak for the Bosnians, as Damir Šolman scored at the buzzer to give the title to Split.

Fueled by that failure and with a new addition—Sabahudin Bilalović—Tanjević and his players won 23 out of 26 games in the 1977–78 season and brought the first major trophy to Skenderija. But they also sought European recognition. That dream was cut short by Partizan, led by Ranko Žeravica and the lethal duo of Dragan Kićanović and Dražen Dalipagić. In an unforgettable all-Yugoslav final in Banja Luka, “Praja” and “Kica” scored 48 and 33 points respectively—enough to overcome Delibašić’s 32 and Varajić’s 22, and Partizan won in overtime, 117–110. The Korać Cup went to Belgrade.

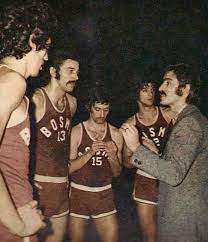

The 1978–79 season didn’t begin ideally for the champions. Mirza returned from Manila as a World Champion but with a serious back injury that forced him to sleep on the floor to endure the excruciating pain. By the time he returned in November, Bosna had already lost valuable ground in the league race. But everyone in the club was waiting for their leader’s return—and once he stepped back on the court healthy, they never looked back.

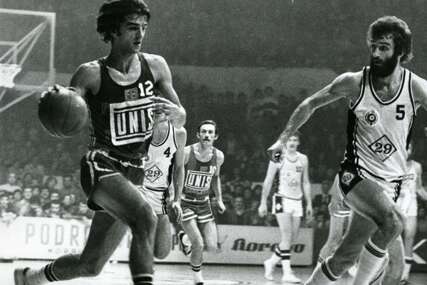

The Yugoslavs won 7 out of 10 games in the European Cup group of six, and on April 5, 1979, they faced the best team in Europe of the 1970s: the legendary Varese of Meneghin and Morse.

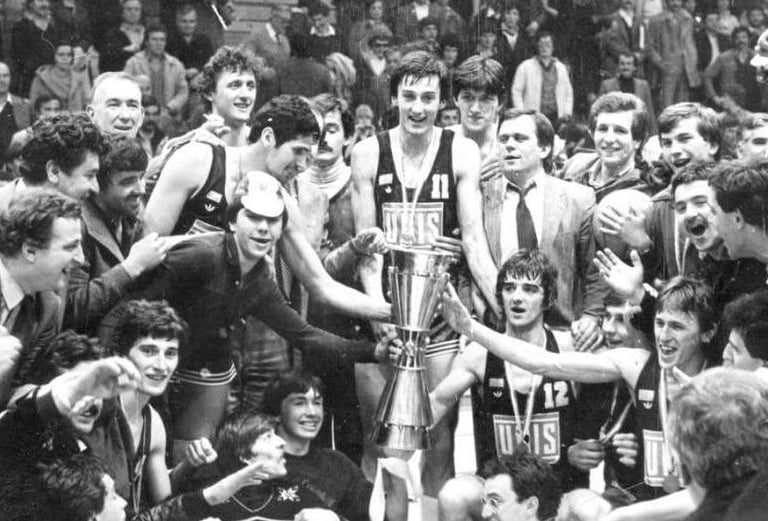

The dynasty of the Italians was nearing its end, but their experience in big games was in their favor, while Bosna had with it the thirst for titles and the fiery eyes of determination. With Delibašić holding the conductor’s baton in his skillful hands and 45-year-old Žarko Varajić as the first violin, the team that just seven years earlier had been playing in the second division was now the new champion of Europe — even if the trophy raised to the sky of the Palais des Sports in Grenoble was borrowed from handball, as the outgoing champions Real Madrid had (!!!) forgotten to send the Champions Cup to the French city. But that didn’t matter to the 10,000 Yugoslavs who gathered at the Sarajevo airport to hail their heroes, and some of them that same night covered the city walls with a chant that would become a favorite in the Skenderija stands. What did it say?

"Šta će nama Kića, šta će nama Praja, tu je nama Kinđe tu je i Varaja"

which means:

"What do we need Kića (Kićanović) for, what do we need Praja (Dalipagić) for, we have Kinđe (Delibašić) and Varaja (Varajić)."

Unfortunately for its fans, Mirza wouldn’t wear the maroon number 12 jersey for long, nor would his mentor. After winning the championship in 1980, Tanjević took the helm of the national team, and Delibašić’s sensitive psyche was left exposed to his weaknesses. Marlboro had become an extension of his fingers and, combined with his daily consumption of his favorite drink, rakija, his stay with the team became more precarious than ever. It was family problems that dealt the final blow. And so, after writing a few words on a cigarette pack, bidding farewell to his wife and son, he left it on the table of his home in Sarajevo and took the first plane to Madrid and Real.

Despite the two major absences, Bosna continued its journey, putting its faith in one of its own. Under Drasko Prodanović, the team ended up just above the relegation zone, and in 1982, Svetislav Pešić was appointed to lead a difficult reconstruction — and he delivered to the fullest. With the former player as coach, Sarajevo’s pride took back the championship crown in 1983, even if it took an intervention from the KSJ (Basketball Federation of Yugoslavia) to overturn the result of the most controversial game in Yugoslav basketball history: the third final against Dražen’s Šibenka. It was the last flash of greatness from the legendary team of the previous decade. Bosna, too, followed the inevitable path of decline as its players, who had gifted it trophies and moments of glory, gradually retired.

Even the return of Mirza as a coach — in an attempt to wrap the team in his personal aura — ended in failure. Delibašić was no Pešić, let alone Tanjević. When the generation of Nenad Marković and Samir Avdić emerged, showing promise for something new, it was war that tragically crushed every hope.

During the siege of Sarajevo — the longest in European history since World War II — Mirza Delibašić became a symbol for his fellow citizens through his resolute stance and refusal to abandon the besieged city.

Even today, the old residents remember him, walking during a lull in the shelling to "Skenderija," with tears in his eyes, talking to Bosnians, giving them strength, because as he said:

"The future of this country lies in the hands of people with pure hearts — and there are many of us."

At the Bare cemetery, where “Kinđe” has rested since December 8, 2001, a Bosna jersey still embraces his tombstone — always reminding us that Sarajevo’s pride thrived because it was, first and foremost, a family. With Bogdan Tanjević as the big brother, as he said in the eulogy when he bid farewell to Mirza — the one he called "my little brother"...