Cantù

"All Europe bowed to a small town"

RETROTEAMS

Antreas Tsemperlidis

6/26/20257 min read

The Garden of the Prophet...

They asked him:

“Il Vate (the Prophet), tell us about triumphs. Tell us about the team that represented a small town and made all of Europe bow before”

"What do you want me to say? Who am I to speak? I am merely a piece of a story that includes creation, devotion, passion, joy, pain, and glory”

Creation... Did you know that Mario Broggi and Angiolino Polli cleared snow with their bare hands from the courtyard of the Sisters of Divine Grace's monastery to create a basketball court? Broggi, his two younger brothers, and their friends were the first athletes of the newly founded club, which was named Associazione Pallacanestro Cantù. However, it was soon renamed to better appeal to Mussolini’s fascist party, which—like all totalitarian regimes—saw sport as a vehicle for propaganda. With a coach pleasing to the authorities, Luigi Cicoria, and under the name Opera Nazionale di Cantù, the team won its first title amid WWII—a cup that flattered the dictator’s vanity and bore his name. The storm of destruction left nothing untouched, including basketball. When the club was re-established in 1949, only the Broggi brothers returned. Their teammates had either died on the battlefield or were severely wounded during the Allied bombings over Italy. A new beginning was necessary, even from the third division. What was needed was devotion.

The brothers set a goal to return to the top and found a worthy ally in a 17-year-old native of the small town. Lino Cappelletti, the team’s first player to become an international, would honor the jersey for thirteen years and take over leadership when the Broggi brothers retired in 1954—by which time the team had earned promotion. This was also when the club began working with sponsors, starting with the distillery Milenka. The fast-growing Italian league—considered Europe’s “El Dorado”—favored such arrangements, and soon, other teams followed suit, such as neighboring Varese and Milan, earning Lombardy the title of the cradle of Italian basketball. Their matches, especially against Rome and Bologna teams, became fierce derbies and decided championships in the 1950s.

During these years, Cantù firmly established itself at the top, and its jersey became highly sought after by investors. In 1956, the Casella family—owners of soft drink factories—jumped at the chance, and the Oransoda brand appeared on the light-blue shirts. Ettore Casella, the family patriarch, was a seasoned businessman. In 1958, he bought the club’s majority shares. But Casella was first and foremost an investor: the year he bought the club, Virtus Bologna advertised Oransoda, while Cantù wore a different brand owned by the magnate—Fonte Levissima. Still, he didn’t leave the club unsupported. His next move brought in a man whose defining trait was passion—the president of championships: Aldo Allievi.

Allievi laid the foundations for a great team, pointed the way to success, and, from 1969 onward, took the club to the top. One of his early moves was to bring in the first significant foreign player: Tony Vlastelica, a reverse-spin magician who claimed not even Bill Russell could block him. He helped the team finish fourth twice—becoming a force to reckon with. As a new decade began, Cappelletti retired, but Charlie Recalcati was already on board—a Milanese transfer who became a masterstroke by Allievi and the missing piece in coach Gianni Corsolini’s puzzle, who had led since 1958. Gradually, the team added the two Albertos—Merlati and De Simone. In 1966, Tauirsano replaced Corsolini and later passed the torch to a young Yugoslav with excellent organizational skills both on and off the court: Borislav Stanković. Stanković brought in Bob Burgess from Real Madrid and, alongside Merlati and De Simone, built the famed “Mura di Cantù” (Wall of Cantù)—all over 2 meters tall—and won the club’s first championship in 1968. The joy years had begun.

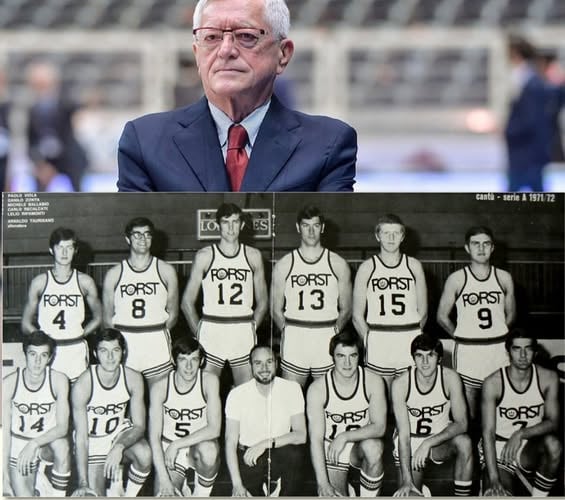

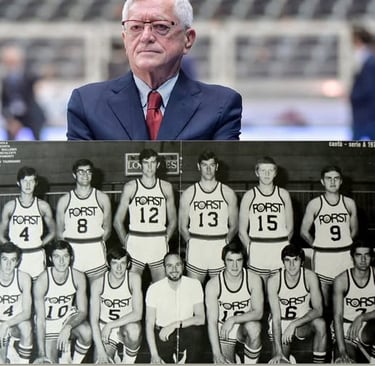

Stanković left in 1969, and Allievi returned as owner. Inspired by his great rival Giovanni Borghi of Varese, Allievi dreamed of building a team with young Italian players. That dream came alive with the arrival of Pierluigi Marzorati, a 17-year-old kid who would wear the blue jersey until age 39 and become a living legend—the “Flying Engineer.” He effectively retired in 2006 at age 54, playing one last game against Treviso—becoming the only player whose career spanned five decades. The coach to lead the charge to the summit was Arnaldo Taurisano, a familiar face. It was a tough task, coinciding with Varese’s absolute dominance. The first thrill came in 1972–73, winning the Korać Cup, the third-tier European trophy, against Belgium’s Maes Pils. They repeated the feat in 1974, playing away due to home court renovations, defeating Partizan Belgrade. The “Biancoselesti” finally claimed the Italian championship in 1975, led by American center Bob Lienhard, the great Della Fiori, Beretta, Marzorati, and captain Recalcati. But first came a historic three-peat in the Korać Cup, including a resounding win over Barcelona, coached by Zeravica. Varese reclaimed the crown, but Cantù began chasing another European title. In 1977, Recalcati lifted the Cup Winners’ Cup after a dramatic final against Radnički Belgrade, coached by Slobodan “Piva” Ivković. Cantù defended the trophy in 1978, beating Virtus Bologna without the injured Lienhard, thanks to NBA champion Hart Wingo. A third straight win in 1979 didn’t surprise anyone anymore. Taurisano and Recalcati exited with honor after that final. Marzorati, Bariviera, Della Fiori, and Americans Johnny Newman and David Batton ensured a farewell worthy of their legacy. Among the jubilant was a young man Taurisano trusted on the roster: Antonello Riva, hardened at just 16 alongside Cantù’s great guards. That era ended in 1979 with six European titles. But the best was yet to come…

“Then Allievi hired you. Why do they call you ‘the Prophet?”

They called me philosopher, innovator, radical… so many names I almost forgot my own. In case you don’t know me, allow me to introduce myself. My name is Valerio Bianchini, and yes, I was the president’s choice for head coach. The team was ready to soar into the heavens of greatness. We kept reaching finals and almost won the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1980, but lost to our Italian nemesis, Varese. We didn’t do well in the league either—only fifth place. Determined after our failure, we started the 1980–81 season with resolve. Riva had matured and taken his place alongside Marzorati, and we had excellent foreign players in Flowers and Boswell. By the end of the season, we were Italian champions and Cup Winners’ Cup holders. We were ready to take the next step, one that would place us firmly in the Bible of the greats. And then, tragedy knocked on my door—for me, the time of pain had arrived. Cantù began its battle to reach the final in Cologne without me. My mind wasn’t on basketball—I could only mourn. My newborn son had passed away suddenly, before I had the chance to enjoy him, to watch him grow, to live.

When I finally managed to get back on my feet, we had already lost significant ground in the championship race, also due to injuries to key players. Europe now seemed like a way out for all of us. The qualification for the final on March 25, 1982, against Maccabi was redemptive. In front of us lay only the road to glory. We were representatives of a small town, facing the symbolic team of an entire nation—David against Goliath. When the game ended, I couldn’t believe we were champions. Cantù was the queen of European basketball. Marzorati, Antonello, “K-Bomb” C.J. Kupec, Beppe Bosa—these men had taken the club to unimaginable heights, beyond anything the club’s founders could have dreamed. I had fulfilled my ambitions and was seeking new challenges. That summer, I left for Rome, Flowers for the NBA, and Kupec for Bergamo. The reins would now be in the hands of a great figure of Italian basketball, Giancarlo Primo.

Two new Americans joined the roster, bringing both experience and enthusiasm: Munich silver medalist Jimmy Brewer and the young Wallace Bryant. On March 24, 1983, in Grenoble, the camera captured one of the sport’s most powerful images. A half-naked Marzorati holding the prestigious trophy high, surrounded by thousands of Cantù fans. But to get there, we needed a deus ex machina—in the form of Brewer, who blocked Gallinari’s shot. That civil war final ended with victory for the provincial side, and defeat for the metropolitan aristocrats of Olimpia Milano. Cantù had written its name in golden letters in the annals of European basketball. In a span of ten years, they played in nine finals, won eight trophies, and became the first team to hold all three European titles. But after the triumph, the “Eagles of Canturina” were never again able to come close to those epic years. Riva was sold to Milan, Marzorati aged, and the last spark came again in the Cup they had first won. In 1991, during the great nights of Pace Mannion, Real Madrid had no answers, and the last European trophy adorned the display at the “Palasport Pianella.”

And then came the decline. Gradually, the team lost its strength, and inevitably, relegation followed. With time, it found its path again—but without the glory of the past. This, then, is the story of Cantù, and I apologize if I’ve tired you. But I had to tell it, because it holds glorious pages that captivate. You know what it reminds me of? A forgotten garden, where among ivy and weeds, rise columns inscribed with names of heroes, tattered banners, rusted trophies.

And anyone who approaches feels a tightening in the heart, a deathly silence. But if one listens carefully, in the distance they will hear victorious chants calling them not to forget. Because though the years may have passed, and the story now seems like shadows—if you can see clearly, the garden of Cantù was magic. And I can only feel honored that I helped it bloom...