Fernando Martín

"Their eternal hero”

RETROPLAYERS

Antreas Tsemperlidis

7/8/20257 min read

A visitor or fan entering the Palacio de Deportes for the first time instinctively lifts their head toward the ceiling, where the banners of dozens of trophies won by the legendary Real Madrid during its glorious journey across Spain and Europe proudly hang. Among them, one jersey with the number 10 stands out—the one and only jersey that “Los Blancos” have ever retired in their long history. And if anyone wonders why out of the hundreds of players -many of whom have been true superstars and legends of the game- who have worn the white jersey Madrid chose to retire this particular number forever, the answer is simple.

Because the man who wore it for two seasons embodied all the qualities that the club’s fans loved: fighting spirit, passion for victory, refusal to accept defeat, and the will to battle until the last second. With these traits, along with his raw talent, Fernando Martín had already secured a place in the hearts of the fans before his tragic end elevated him to the realm of legend. Martín was one of those rare, true athletes who seemed born for multiple sports. Swimming (with distinctions), handball, and table tennis, alongside basketball, were the sports in which the pure Castilian Fernando excelled until the age of 17.

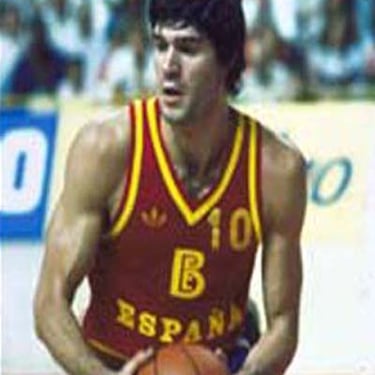

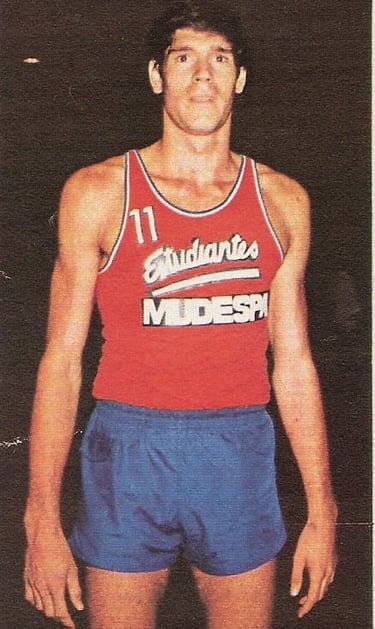

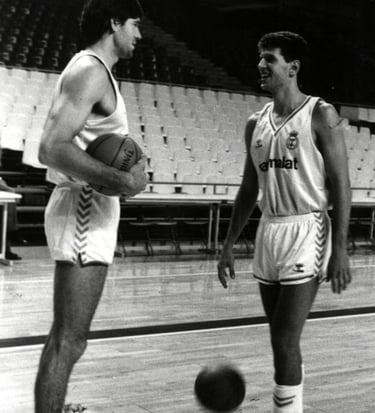

In 1979, as a player for Estudiantes, he was called up to the Spanish national team for the European Cadet Championship in Damascus. The coach who would later try to find ways to stop him, Aíto García Reneses, could hardly believe his eyes watching Martín dominate both ends of the court, leading Spain to a bronze medal. The same story repeated at the European Junior Championship the following year in Yugoslavia. After two seasons as a starter with Estudiantes, Spain’s new basketball diamond was ready for the next step. Real Madrid moved faster than all the other big clubs vying for him, ignoring rumors that Badalona had already signed a pre-contract, and Fernando, who had already debuted with the senior national team on May 13, 1981, became a part of the squad, playing alongside greats like Corbalán, Brabender, and Iturriaga. Partnering in the paint with Fernando Romay, the young Martín won the first of his four career league titles and provided coach Díaz with an additional weapon for the World Championship in Colombia, where Spain came close to a podium finish. The 20-year-old Spaniard scored 21 points in the third-place game, but Yugoslavia edged them out by a single basket.

He was well on the path to greatness, and the spotlight was now fully on him as he was considered Europe’s next basketball star. He did not disappoint any of his admirers and began building his basketball legacy as if he already knew his future. He wanted titles and medals, and by 1986, he had won almost everything. With “La Furia Roja,” he captured silver at EuroBasket 1983 and the 1984 Olympic Games, while with Real, he won three consecutive league titles from 1984 to 1986 and the Cup Winners’ Cup in the final in Ostend. In that Belgian city, his battle with Dino Meneghin of Olimpia Milano became one of those historic European final duels. The experienced Dino struggled against the young Martín, who was unfazed by the Italian’s infamous elbows and fought him just as hard, taking revenge for the lost 1983 final in Nantes. In between, Martín and Real made an unsuccessful run at an eighth European Champions Cup, but in 1985, the SEF floor belonged to Dražen and Cibona. After the 1986 league title and the World Championship held in Spain, the 24-year-old Martín, who in five years with Madrid had already reached the elite of European basketball, felt ready to travel to the birthplace of the sport.

He had wanted this journey since 1985, the year the Nets drafted him at number 38. His name was on the passenger list of the Iberia flight on August 21. Fernando, who was running late, borrowed the Mercedes of national team coach Antonio Díaz Miguel. The accident that occurred on the way to the airport left him unharmed but postponed his NBA entry by a year. When he finally went to America, it was as a free agent since the Nets had not retained his rights, and Fernando signed with the Blazers, becoming the second European to play in the NBA without having attended college, after Bulgaria’s Georgi Glouchkov. His time in the NBA barely fills five lines. At that time, European players seemed to Americans like an exotic fruit they hesitated to taste. The word “skepticism” is a polite way to describe how Portland treated Martín. Coach Mike Schuler trusted one of Europe’s best big men with just 25 games and 147 minutes. That says it all about his NBA stint. Injuries and homesickness also played a decisive role, and our hero returned home in the summer of 1987.

Real Madrid welcomed its beloved son back, and Fernando opened his wings for new triumphs. His second stint with his beloved club was as successful as the first, though not as much domestically, as it coincided with Barcelona’s rise—his duels with Audie Norris were legendary, with Norris admitting that Martín brought out the best in him—but certainly in Europe. They began with the 1988 Korać Cup against Cibona, exorcising the “nightmare” of 1985, Dražen Petrović. Due to injury, Fernando did not play in the two finals, watching from the stands as Petrović tried to steal the trophy in the second game, scoring 47 points. His role became much more active the following year at the Peace and Friendship stadium, playing alongside the “Son of the Devil” (Petrović), witnessing his performance in the 1989 Cup Winners’ Cup final victory. Fernando’s contribution? 11 points, 7 rebounds, and a tough battle with his old acquaintance Glouchkov. Embracing Petrović, they celebrated the trophy, unaware of the tragic fate that would soon unite them.

On December 3, 1989, Fernando Martín was left out of Real’s twelve-man squad for the game against Zaragoza due to back discomfort. His last game had been against Granollers two weeks prior. The night before, he had dinner with the team’s physiotherapist, Paco López, who later recalled how Fernando was in high spirits, happy about the imminent arrival in Madrid of his five-year-old son Jan, whom he had with former Miss Israel Petra Sonnenborn and who lived with his mother in Tel Aviv. They never met again.

He arranged with his friend Kiki Villalobos to drive together to the game in Martín’s bright red Lancia Thema, which he had modified with a Ferrari engine. On Madrid’s M30 ring road, driving at breakneck speed, he tried to take the exit to the arena. For unknown reasons, the car crossed into the opposite lane and collided head-on with a vehicle driven by Spanish painter Ricardo Delgado, who was seriously injured. At the moment of the crash (3:15 p.m.), Martín was not wearing a seatbelt and suffered fatal head injuries. He passed away in the ambulance on the way to Ramon y Cajal Hospital. At his funeral, the entire Spanish basketball community accompanied him to his final resting place, with teammates and opponents alike shattered, trying to comfort the family.

Two days after the tragedy, in an arena that felt like a cemetery, Real faced PAOK. Both teams and FIBA had agreed to postpone the game, but Real’s players, including his brother Antonio, insisted on playing, believing it was the best way to honor Fernando’s memory.Real’s coach was George Karl, the future Sonics coach that would end up tallying 1,175 NBA wins. Karl still considers that game the most important of his career and, as he claims, the only one he ever coached drunk! The game began, but no one was really watching. All eyes were on the Real bench, where Fernando’s number 10 jersey lay carefully, with a bouquet of white flowers placed on top. The shocked Real players played like they were in a trance, and PAOK took advantage, leading 46-33 at halftime. In the Madrid locker room, there was dead silence, with everyone waiting in vain to hear Fernando’s strong voice lifting their spirits. Instead, they heard his brother Antonio scolding them, saying: “Fernando thinks you’re kittens (a polite translation for putas). If he were here, he would be slapping you right now.” Psychological trick or not, it worked perfectly in the second half. The kittens transformed into lions, and the court tilted in Real’s favor. The tragic hero, his brother, led the comeback, as the fans cried, seeing that while Fernando was gone, his spirit was still there.

He may not have been the best player in the world, but he understood better than anyone the weight of that jersey. Every time he stepped onto the court wearing it, everyone knew he was ready to “die” for it. He hated losing, but even more, he hated losing without fighting. At just 27 years old, the star of Fernando Martín set while he still had so much more to give to Real, to Spain, and to European basketball.

That cold December night, the fans of “Los Blancos” felt the presence of their leader and shouted it with all their strength:

“Fernando estás aquí “ (Fernando, you are here).

He was one of them, their eternal hero - He was their Fernando Martín.