Final Four - Athens 1993

"The Night Basketball Changed"

RETROFFF (FINAL FOUR FOLKLORE)

Antreas Tsemperlidis

5/6/20255 min read

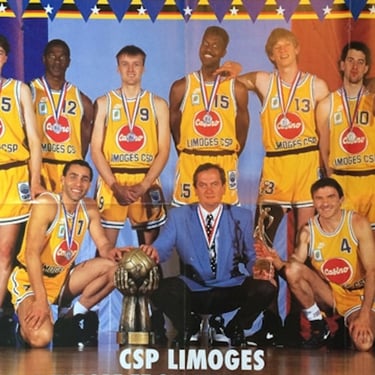

On the night of April 15, 1993, the hardwood floor of the Peace and Friendship Stadium was drenched in emotion. As Richard Dacoury lifted the European Champions Cup trophy high above his head, a tearful Toni Kukoč, already halfway to the NBA in his mind, watched his beloved coach claim glory in a way completely foreign to the poetic style that had twice taken Jugoplastika to the top. From the futuristic basketball of Split’s dynasty, Božidar Maljković had pivoted to the extreme opposite: an all-out war of 30-second offensive grinds, a strict ban on fast breaks, and bone-rattling defense. That was his doctrine — widely criticized, often mocked, but ultimately triumphant. Limoges had done the unthinkable. They were champions.

Moving on to Athens and 1993. The FFF journey with a twist of fate... Lets roll back the years once more. Here is how the F4 story continued to unfold...

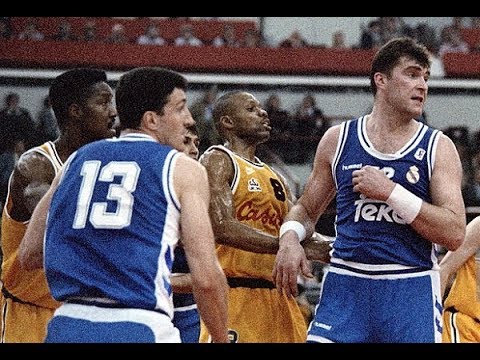

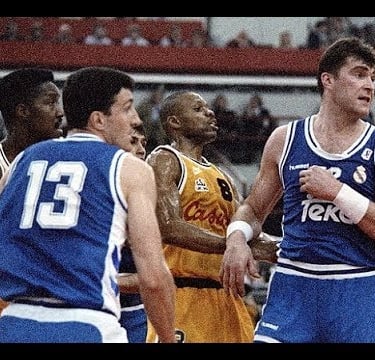

It was the only way they could overcome the three other contenders, all arguably more talented — starting with their semifinal opponent: Real Madrid. “The Queen of Europe” entered the court exuding confidence, ready to flaunt its crisp passing, fast tempo, and the dominance of Sabonis in the paint. Instead, they slammed into a French defensive wall that allowed them only 35 possessions — most of them forced, frantic, and desperate. Still, Limoges had to put points on the board. That’s when Michael Young, the sharpshooter from Houston, stepped in. As for Arvydas? Despite being hacked relentlessly by Redden and Bitter, he fought valiantly with 19 points & 10 rebounds — but it wasn’t enough. At the final buzzer, it was the French side celebrating and with them, 12,000 PAOK fans in the stands, jubilant. They believed, perhaps rightly, that the title was theirs for the taking. And who could blame them? The PAOK of 1992–93 was one of Europe’s elite, boasting the continent’s most complete starting five: Korfas and Prelević orchestrating and executing with deadly precision; Barlow, Livingston, and Fasoulas forming an impenetrable frontline.

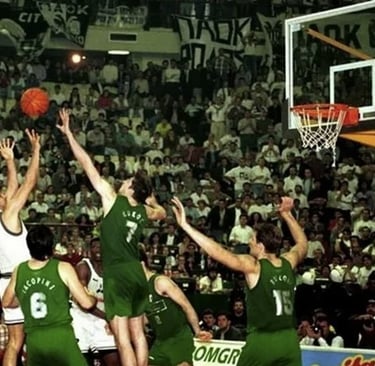

Benetton may have had Kukoč, but PAOK had the balance and firepower to control the game. But just as in life, basketball always reserves a place for the unpredictable. In this case, its name was Maurizio Ragazzi. Or if you prefer divine irony: Fate and the overturned car of Christos Tsekos a week before the Final Four. What do I remember from that semifinal? First, the masterclass of Toni Kukoč with 15 points, 10 boards, 8 assists, capped by a monstrous dunk right in Fasoulas’ face. “Pani” was in foul trouble early and had three by halftime. The clumsy but mighty Rusconi ran riot under the basket, feasting on Toni’s laser-like feeds. Had PAOK had Tsekos -sidelined by that infamous traffic accident- perhaps the defensive matchups & adjustments would’ve been easier. Maybe we’d never have witnessed those three back-to-back daggers from Massimo Iacopini, who turned into “Pistolini” for a night and gunned down the Greek hopes. And then came that final nail in the coffin... Ragazzi’s corner jumper with three seconds left, left completely unmarked as PAOK’s defense collapsed on Kukoč. Of course, no recounting is complete without calling out the unforgivable decision by ERT -Greece’s national broadcaster- to cut to commercials during PAOK’s final, potentially game-winning possession!!! Instead of watching it live, we saw a replay of Bane launching a desperate heave from half court, still disputing whether Dušan Ivković had drawn the play for Livingston or the wide-open Korfas. The result, though, was undisputed and merciless: 79–77. A bitter loss. The greatest missed opportunity (up to that point) for Greek basketball to lift the European crown given the home court advantage.

So, instead of the two favorites, the court was now set for the two underdogs. Logic said Benetton would win it, but often basketball laughs in the face of logic.

The game began with Zdovc glued onto Kukoč, but it was American Terry Teagle who did the early damage for the Italians, dropping 13 points in as many minutes. Maljković turned to Dacoury, his grizzled veteran who handcuffed the former Laker with old-school defense. With "The Blond Hound" hounding him, Kukoč couldn’t find his rhythm, opting to pass instead. That left Rusconi, the semifinal hero, shouldering the burden. For Limoges, it was all about feeding Young and hoping for divine intervention and the French ended up trailing by six at the break. The second half continued the gruesome basketball of the first, but then, out of nowhere, emerged an unlikely hero: Jim Bilba. Not only did he score 15 points, mostly off second-chance efforts, but he locked down Rusconi, and when Zdovc got evidently tired, he even took on Kukoč.

Slowly, the French clawed back. Then, Kukoč decided enough was enough. With three consecutive threes, the “Spider of Split” dragged Benetton back into it. Everyone knew who would take the final shot. Kukoč initiated the play with Zdovc draped over him like a shadow. He reached the top of the key, coming off screens, facing Forte. Two options: drive or pull the trigger. Just as he seemed poised to shoot… Forte stripped him clean. In the free throw roulette that followed, Limoges were ice-cold. The final whistle blew, and to the stunned disbelief of most, they were champions of Europe.

The Italians cried foul, protested the physicality and the refereeing but it was over. Inside a half-empty stadium -the PAOK faithful having walked out in protest at halftime- Boris Stanković handed the trophy to the ultimate underdog. And Maljković, normally stoic, cracked a faint smile. It was vindication. But who could blame Petar Skansi, Benetton’s coach, when he said:

"Tonight, basketball died. If this is the future, I’ll open a pizzeria."

To which Boža might’ve replied:

“When I had Kukoč, you saw the basketball my teams played.”

And honestly? He had a point. Outside of Zdovc, Young, Dacoury, Forte, and the athleticism of Bilba, the rest of Limoges looked anything but like basketball players. Maljković simply had to find another way. And that way was “strangulation.” That method and its mindset would come to dominate the years that followed. The era of 100-point games was over. European basketball had taken a sharp turn.

And maybe, just maybe, that night, some quietly whispered the words of Edward R. Murrow:

“Good night, and good luck.”