Radmilo Mišović

"The “Prince of Morava”

RETROPLAYERS

Antreas Tsemperlidis

10/6/20255 min read

Let’s do a quiz. The question? Who do you think is the all-time top scorer in the history of the former Yugoslav basketball league?

I assume that the obvious answers come to mind: Dražen and Korać, Dalipagić with Kićanović and Delibašić; the older ones might say Đerđa and Plećaš, while the younger ones might think of Danilović and Komazec.

I don’t blame you, I would think of the same names too, if I didn’t know the story of Radmilo Mišović, the man who, with 7,456 points, is and will forever remain the holder of a record that will never be broken.

Is this the first time you’re reading Mišović’s name? Understandable. Radmilo never left Čačak, he was never called up to a major tournament by the national selectors, and during his career, he only ever wore the number 11 jersey of Borac. Even when he came close to transferring to Partizan, he only lasted two months away from Čačak and the Morava River where he loved to fish. His Ithaca was always his hometown, on the parquet of Borčevo, and he paid for that choice with the label “a great player for a small team.” “The Prince of Morava,” as Borac’s fans named him, was born in Čačak on March 14, 1943, the third child of Jovan and Milica, in the same house where his father had been born, just a few blocks away from the Orthodox Metropolitan Cathedral of the Ascension, which tradition says was built in the 12th century by Stefan Nemanja himself. Radmilo’s family had sports in their blood; his father played football, and all four of his siblings, boys and girls, were involved in basketball. In such an environment, it wasn’t hard for him to channel the energy of a teenager by starting with gymnastics, basketball, and even handball. He was 10 years old when one day, at a court near his home, he saw a group of older boys shooting hoops. As soon as they left, he tried to do the same, but his first attempt ended in complete failure. Yet he didn’t get discouraged, every afternoon, he would be on that concrete court, trying to replicate what he saw from Borac’s stars of the time: Bole Denić, Aco Stefanović, and Srećko Igontinović.

In 1958, as a member of the youth team, he would be on the court chalking the lines himself, as it was the closest he could get to the men’s team. When he finished, coach Kembo Smiljanić informed him that the next day he would be playing in the local derby against Železničar.

Overjoyed by the news, he went for a swim in the Morava, and during a dive, he hit his head, but he still showed up on the court with a bandage covering his wound. There was no way he would miss his debut. Not only did he play, but he also scored the first two points of his career with a shot that turned out to be the game-winner. The seed was planted, and six months later, at a tournament in Titovo Užice featuring Crvena Zvezda, Radnički, Železničar, and Borac, and after receiving special permission to play against first-division teams since he was underage, he emerged as the tournament’s top scorer before he had even turned 16.

But there was also handball. Simultaneously with basketball, he played for Remont and was so good that he was considered the best player of his age in Čačak. In 1961, Remont, as the Western Zone champion, competed in a playoff for promotion to the first division but fell short. In the decisive match held in Čačak against a team from Belgrade, they lost 26-20, with Radmilo, despite the loss, being the standout player on the court.

In the fall of 1961, Mladost, a first-division handball team, brought him to Belgrade, and Mišović started training with them, but fate had other plans for him. Basketball was waiting.

He returned to Čačak and rejoined coach Stefanović, becoming the most dangerous weapon in his coach’s arsenal in the quest for promotion to the top tier of Yugoslav basketball. He was so good that in 1962, he was called up to the Yugoslav B national team, the only player from a lower division and just 19 years old. By then, he was recognized as the de facto leader of his team and Borac’s biggest hope to reach the elite level. This journey nearly ended in 1964 when Partizan called him to Belgrade for trials. Although he impressed during training, his longing for Čačak led him to refuse to sign a contract with the Crno-Beli. Years later, when asked if he ever regretted it, he would reply no, saying, “At Partizan, they wanted my shot, not me as a person. I was 21, and I missed home. I looked out the window of my room in Belgrade, first to the left, then to the right, and I didn’t see anything familiar. Here, I see the Morava, and that’s why I returned to Čačak.”

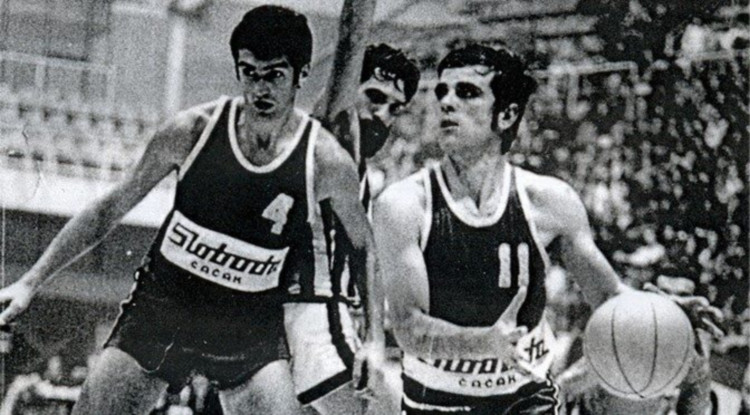

Eventually, promotion was achieved in 1965, and for the next eleven years, with Mišović scoring at a relentless pace, Borac established itself in the first division. All the big teams lost at Borčevo, and this 1.83m guard was truly unstoppable, as evidenced by his five top scorer titles and his duels with the big guns: Dalipagić, Šolman, and Kićanović, who had idolized him when they both played for Borac.

And here arises the question of why this great scorer was not a regular in the national team, with his presence for the Plavi limited to four appearances in the 1966 Balkan Championships.

In 1970, Žeravica called him up for preparations ahead of the World Championship in Ljubljana. Everyone believed Radmilo would finally make the final roster and show his capabilities at the highest level. His omission came as a surprise, but Žeravica explained it in a way that perhaps reveals the answer. Ranko said, “Milo is an incredible scorer, perhaps the best in Yugoslavia. But he’s used to a different style of play; in the national team, he can’t take 15 shots, and that would be unfair to him and his teammates.”

Perhaps that was the case. Mišović’s career showed that he needed the ball in his hands to score prolifically, but on the other hand, can you name a great scorer who took few shots during a game? I believe Radmilo deserved a chance, but he never got it.

When he ended his career in 1978 with his beloved Borac, this was the only regret that remained, but the love his compatriots still show him today, and the respect from figures like Obradović and Kićanović, sweeten the bitterness for the “Prince of Morava,” Radmilo Mišović…