Radomir Šaper

"The Greek Plavi"

RETROCOACHES

Antreas Tsemperlidis

12/28/202510 min read

An excellent student, his future seemed bright in the academic world—until one day in 1938, when Professor Doka Ilić happened to be in a good mood (a rare occurrence) and handed a ball to Raša and his classmates with the simple order: “Start.” But start what? Ilić didn’t bother explaining the rules, and as Šaper later recalled, “Our game was a mix of handball and rugby. We threw the ball to each other, and to take it from someone you had to hit them. And once you got it, you ran toward what was supposedly the basket, trying to put it in.” Even under these primitive conditions, the young boy fell in love with the sport and his brother shared the same passion. Walking home from school, they would pass the ball between themselves, an invisible ball, or take defensive and offensive positions, ignoring the strange looks from passersby. It was this imagination that eventually led them to a real court. The outbreak of World War II, the German invasion, and Nazi occupation of Yugoslavia did not stop the Šaper brothers from playing basketball. In 1942, along with Boža Mučan, Dušan Kening, and Luka Denić—all students at the Second Gymnasium—they joined the ranks of BASK, and in the spring played their first game at Tašmajdan against the more seasoned team of the “King Alexander I” Gymnasium. Among them was Nebojša Popović. Their first match ended in a crushing defeat. Watching that game, while playing tennis nearby, was Borislav Stanković, who then decided to join BASK. “None of us really knew the rules,” Stanković later recalled. “An Italian prisoner of war who was at Tašmajdan showed us some things. The biggest problem was dribbling—the Italian insisted we couldn’t run while holding the ball.” Little by little, the youngsters absorbed the rules and improved. It was Nebojša Popović who translated the rules and suggested the idea of the first unofficial championship among Belgrade teams in the autumn of ’42, on the sacred ground of Yugoslav basketball, soaked with sweat.

They say that whichever stone you lift, you’ll find a Greek underneath...

Even in the history of Yugoslav basketball, we had a hand in it—albeit indirectly—through the origins of Radomir Šaper, born on December 9, 1925, the man who, behind the closed doors of his office, worked day and night together with the other members of the “Holy Quartet” to bring to life the miracle of the "Plavi". As Šaper himself maintained, “Nothing in our basketball happened because of one person alone. Every success was the result of teamwork, from players, coaches, and us, the officials, the former basketball players.” But what was Raša’s connection with Greece? The closest possible, as his father Panagiotis Siaperas was a Greek from Eratyra, Kozani. Together with his brother Konstantinos, he owned a commercial store in Thessaloniki and often traveled to Belgrade for work. When the two brothers decided to expand their business activities, it was Panagiotis who, in 1919, opened the store on Vasiņa Street, and to earn the trust of his customers, he decided to Slavicize his name. Thus, Panagiotis Siaperas became Panta Šaper, and after his marriage to Vuka Mihajlović and the birth of Svetislav in 1923 and Radomir in 1925, it became clear that his life would continue in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, in their home on Stefan Sremac Street.

But fate had other plans for the Šaper family, and it proved cruel. In 1927, Panagiotis died of pneumonia, and Vuka, devastated by the loss, collapsed psychologically. The two children went to live with their maternal grandparents, Taško and Sofia Mihajlović. In 1931, Radomir began school at the Vuk Karadžić Elementary School, until 1937, when he enrolled in secondary education.

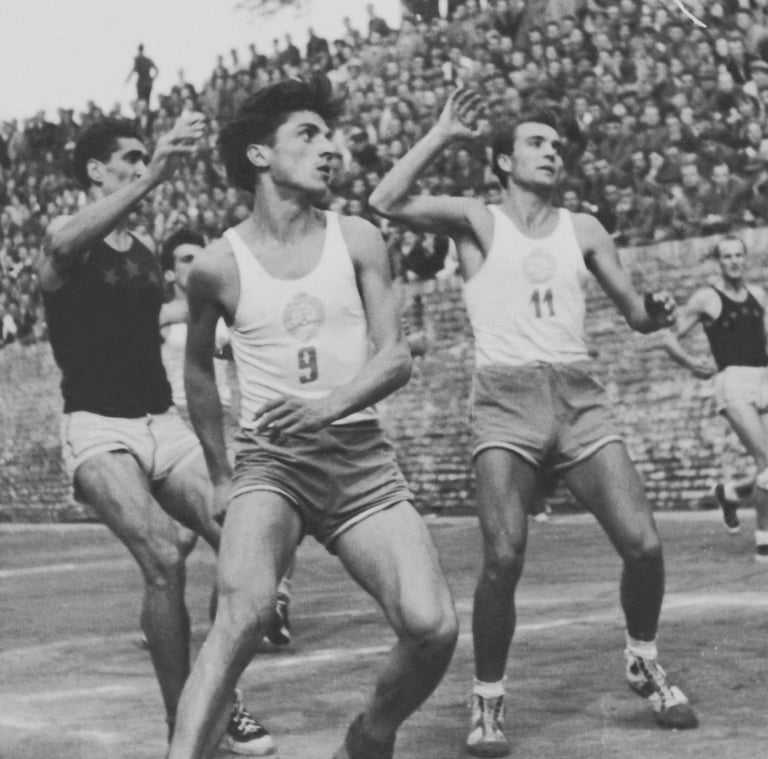

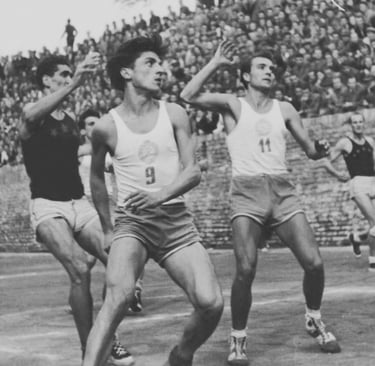

Kalemegdan became the meeting place of the "Holy Quartet": Šaper and Stanković with BASK, Popović with SK 13, and Aleksandar Nikolić with Obilić. Teenagers of 17 and 18, unaware that on that red clay they were writing the prologue to a golden chapter of history. But the invisible author’s pen paused for a time when Raša and his friends were recruited in October 1944 and sent to fight on the Srem front, along with the rest of Yugoslavia’s youth, many without even basic military training. Radomir survived and returned to Belgrade; thousands of young Yugoslavs remained forever on that front, defending their homeland’s freedom. The Šaper generation matured abruptly in the trenches of death. They saw horror with their own eyes, and when they returned, their purpose was to embrace life fully. Raša chose basketball. As soon as he set foot in Belgrade, he ran to Kalemegdan, and with his friends began clearing the court. When they finished, they found an iron pole, attached a wooden backboard and a rim, and Yugoslav basketball was reborn from its ashes. In March 1945, Red Star (Crvena zvezda) was founded, and the best players of Belgrade joined the team. In April, a game was held in Kalemegdan among its athletes. Šaper was the only one wearing athletic shoes—specifically, boxing shoes. The rest played either barefoot or in hard military boots. Four months later, Red Star received an invitation to travel to Subotica for the first national championship. They lacked proper equipment—they didn’t even have a real basketball—but their enthusiasm overflowed. Red Star’s players were ready to defeat all rivals. Understandably so: they had the best—the Šaper brothers, Nebojša Popović, Miodrag Stefanović, and Aleksandar Nikolić. Convinced the title was theirs, they went to Subotica, only to encounter a surprise. The organizer, Colonel Ratko Vlahović, informed them that Nikolić was still a member of the Yugoslav Militia and therefore had to play with the Army’s team, JNA. He had no right to refuse. Not only did he play, but he also scored the four decisive points that gave the Army team the victory, 21–16. Immediately afterward, he was discharged from the Militia.

Šaper and Nikolić returned to Belgrade, still in ruins, and at Nikolić’s home on Kosovska Street the four friends decided they must remain united under Red Star’s banner. Most importantly, they wanted to work for the progress of their team—starting with the basics like shoes and balls, luxuries in a country devastated by war. They found a ball—even a soccer ball—and canvas shoes with rubber soles. Red Star’s first starting five—Radomir Šaper, Aleksandar Nikolić, Borislav Stanković, Miodrag Stefanović, and player-coach Nebojša Popović—wanted to play together. Seven months later, in October 1945, the Army founded its great rival, Partizan. Red Star’s players believed they were ready for battles—until reality intervened. One day, Vlahović—now even more powerful in basketball affairs—approached the Šaper brothers with a telegram. Reading it, they learned they had not yet completed their military service and were obligated to join the Army’s team, Partizan. Unable to refuse, the two guard brothers walked a few steps from Red Star’s facilities to Partizan’s. They would remain there for the rest of their basketball careers.

Because life comes full circle, Radomir made the big decision to retire as a player in 1953 during a derby against Red Star. As he said, “We were playing against Red Star when a group of fans did what I consider the most unpleasant thing for an athlete anywhere in the world. They booed me. At first I was angry, but then I realized it was time for me to withdraw.” Raša could now devote himself to his academic career and to the family he had started with the beautiful woman he met in 1948—Lidijana Marjanović, the sweet protagonist of one of the first films in Yugoslav cinema history, "Besmrtna mladost" (Immortal Youth). But the “microbe” of basketball was deeply rooted in him and in the other members of the “Holy Quartet”—and the oath they had taken in Buenos Aires would not let them rest. In January 1950, the four traveled to Nice, France, as national team players to compete in a qualifying tournament against the hosts, Italy, Spain, and Belgium, for two spots in the first World Championship in Argentina. France qualified automatically, and the others fought for the remaining places. Yugoslavia lost to Italy and Spain, beat only Belgium, and was eliminated. But as they prepared to return to Belgrade, they learned Italy refused to travel to South America, and the spot was theirs if they wanted it.

The Plavi accepted and went to Buenos Aires—only to finish last, in 10th place, losing every game, including one by forfeit, after orders from above not to play Spain. The official reason cited the lack of diplomatic relations; the unofficial one suggested the Communist Party wanted to avoid another humiliation. The shameful 10th place wounded the pride of the four friends but also showed them how far behind they were. If they wanted to catch up and surpass the world, they had to rebuild Yugoslav basketball from scratch. In the locker room of Luna Park arena, they joined hands and swore they would reach the summit of the world. Their time came in 1953 when the last active player among them, Stanković, retired after the European Championship in Moscow, where Yugoslavia finished 6th. The next year, at the World Championship in Rio, they attended as spectators, watching their team finish again at the bottom (11th). The gold medal went to the Americans, who hadn’t even sent their best players. As Danilo Knežević, head of the KSJ, remarked: “The gold medal was won by a group of factory workers from Detroit. I wonder how the real basketball players would play.”

He posed this question to the four young men he summoned to his office, and after listening closely to their vision, he gave them complete freedom. That was the moment. The quartet rolled up their sleeves and plunged into work, taking three fundamental decisions:

1. Basketball must be established and developed in specific cities (Belgrade, Zrenjanin, Čačak, Kragujevac, Zagreb, Karlovac, Zadar, and Ljubljana).

2. Anyone with any useful idea must be given a place and a voice in the Federation.

3. France and Czechoslovakia had been Yugoslavia’s basketball models, but their time had passed. Better teachers now existed—Americans, for example—and from them Yugoslavia must learn.

The phrase that defined the Plavi, “basketball for the basketball players,” was born. They had learned the lesson of Rio. Nikolić was appointed national selector; Stanković and Popović took over the best clubs. But it was Šaper who rose to the top of the KSJ, first as head of the Technical Committee and later as vice president. Knežević was preparing his successor.

The quartet devoted themselves to the cause. They worked tirelessly, and in the 1960s the first medals arrived. Basketball made its presence felt. The sport was cementing itself in the public consciousness. In 1965, Knežević resigned as president of the KSJ, leaving behind success. Unlike usual practice, his successor was not a political appointee. This time the choice came from within the sport from someone who knew its needs better than his own palm, who had been in the Federation since the beginning and lived basketball every day. Forty-year-old Radomir Šaper became the first former national player to become president of a sports federation in post-war Yugoslavia. Under Šaper’s leadership, Yugoslav basketball entered new paths of “professionalism.” Everyone worked for its progress, with the 1970 World Championship in five host cities ahead. As a former player, he understood the need to keep veterans close, to pass on knowledge and experience. He gave them responsibilities; he empowered them. In cooperation with coach Žeravica, he masterfully handled the psychological shock after the tragic death of Krešimir Ćosić. On May 23, 1970, he was in the stands of Hala Tivoli in Ljubljana for the decisive match against the United States for the gold medal. Before tip-off, he handed Žeravica a telegram from the students of the Technical School of Smederevo. It contained four words, completely clear in meaning: “Play for Korac.” With that extra motivation, and with 5,000 compatriots creating an electric atmosphere, Yugoslavia found the strength to win—and become World Champions.

As Ćosić, Daneu, Skansi, and their teammates hung the gold medals around their necks, four greying men once again joined hands with tears in their eyes. The oath they had taken twenty years earlier had been fulfilled. After the World Championship victory, Yugoslavia became the main rival of the previously dominant Soviets. The “Golden Decade” of the ’70s and the continuous production of talent proved the excellence of Šaper and his colleagues. Their decisions were law and success confirmed them. It is no coincidence that no one challenged Šaper in KSJ elections. His authority came not from political identity but from achievements. Raša had never been a member of the Communist Party; he always openly embraced democratic beliefs. When the Plavi reached the summit of the Olympic Everest after the Moscow Games of 1980, Šaper intensified his work as president of FIBA’s Technical Committee, a position he had held since 1972. With his proposal, world basketball changed forever when FIBA adopted the three-point line. He vigorously supported the rapprochement between the NBA and FIBA, backing Borislav Stanković and David Stern. He believed in the globalization of the game. Above all, though, he remained Yugoslav and president of the KSJ. From this position, he saw new talents emerging and supported them after the 1986 semifinal in Madrid, declaring:

“We must have faith in these new boys and give them a chance. They need at least 30 international games per year to gain experience so we can get the best out of them. Let them lose a few—how do you expect to build a new team if they are constantly pressured to win every game? Our history and reputation will not be destroyed every time these kids step on the court. Let them breathe.”

He knew the material he had. He saw that this generation was one of the best Yugoslavia ever produced. And time proved him right, in the brief years the country remained united. When the clouds of civil war began gathering, he and Stanković were the first to try to save whatever could be saved. He believed basketball must stay outside conflict. He was an idealist—but also a man who had seen the horror of war firsthand. He failed; in a country collapsing, where former brothers waited to drive the knife deeper, there was no room for sentiment. His name, however, remained untarnished across the former Yugoslavia. Milorad Bibić, a former referee, recalled a story: during the civil war, Croatian soldiers sought shelter in a provincial basketball gym. Searching the offices, a soldier found a photograph including Šaper. He spat on it, cursing Raša, only to face the fury of his commander, who reprimanded him, cleaned the photo, and hung it back in its place, showing respect to a man whose work had once made him celebrate. Šaper continued working for the progress of Serbian basketball even though he failed to convince the IOC and FIBA in 1992 to lift the unfair ban from the Olympics and all international competitions. Everyone respected him, no one wanted to listen.

He did not lose heart. He celebrated Serbia’s return to European and world dominance. Until December 6, 1998, he attended youth championship games, scanning the new generation. That was where a stroke struck him down, three days before his 73rd birthday. All of former Yugoslav basketball honored his memory from Slovenia to Skopje, every arena held a minute of silence.

Because basketball was the life of Radomir Šaper, his great love until the very end.