Ranko Žeravica

"The beloved dictator”

RETROCOACHES

Antreas Tsemperlidis

7/10/20257 min read

Even today, basketball leaders with roots in the former Yugoslavia find themselves following one of the two “factions” of the Plavi coaching school. The first was born within the walls of Kalemegdan, personified in the figure of the “Professor” Aca Nikolić. The second was created in the triangle of Crveni Krst, expressed mainly by the “Dictator” Ranko Žeravica, who had a relationship of rivalry but also deep mutual respect with Nikolić.

Žeravica had the reputation of being a tough coach, a “tyrant” of the court, as his basketball “children” remember him, many of whom also played in Greece. Those who knew him from a young age, however, were not surprised by his harshness but rather saw it as a natural consequence of the hardships Ranko encountered in his life. As a child, he experienced the horrors of war and occupation, hunger, and hardship. Each day was a struggle for survival, with death seeming more likely than life. In the Žeravica family farmhouse in Dragutinovo, the only furniture left after the continuous “visits” from the Nazis and Tito’s Partisans was a table and the bed on which Ranko and his mother, Ljubinka, slept. His father, Milorad, was imprisoned in a German concentration camp, and when he returned to Yugoslavia in 1945, he was imprisoned again for “re-formation.” At 16, Ranko had to work in the fields to support himself and his mother, with the hoe and sickle becoming tools of survival in his hands.

It was hard work until that day in 1945 when a unit of the KNOJ (Korpus Narodne Odbrane Jugoslavije) led by a man nicknamed “Džibanika” arrived in the village. Inside his sack of ammunition, the officer hid something else.... A basketball, which instantly fascinated young Ranko. He wanted to learn, to play this beautiful game just as the partisans did in his village square, but to do so, he had to walk daily the 20 km distance between Dragutinovo and Kikinda, where the team “October 6th” was based. His determination was immense, and for two years, he walked the 40 km daily without complaint while also working the fields, earning just enough for a plate of food. When he realized his future was to die as a farmer in Dragutinovo, he preferred to die, at least, as a student in Belgrade. He was 18 in 1947 when he went to the capital to take the entry-exams for the Polytechnical School, aiming for a degree in Mechanical Engineering, but what had ever come easily in his life to expect this would? A party representative informed him that his father was registered as an “enemy of the state,” and therefore, they could not allow the son of a “traitor” to enter the educational institution.

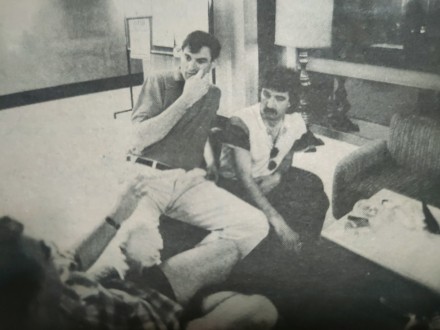

Disappointed by the rejection and unwilling to return to Dragutinovo, Žeravica wandered the streets of Belgrade looking for work, and at night, with nowhere else to sleep, he found refuge in the waiting hall of the train station. His steps eventually took him to the neighborhood of Crveni Krst, the base of Radnički. He asked to train with the team, and when they told him he could stay, he asked if there was a place where he could sleep. They gave him a small storeroom, and a mat used by wrestlers for training, which, compared to the train station bench, seemed like a five-star hotel to him. He stayed in that storeroom for four months until he accidentally met his godfather on the street, who took him into his home, providing him with food and a bed.

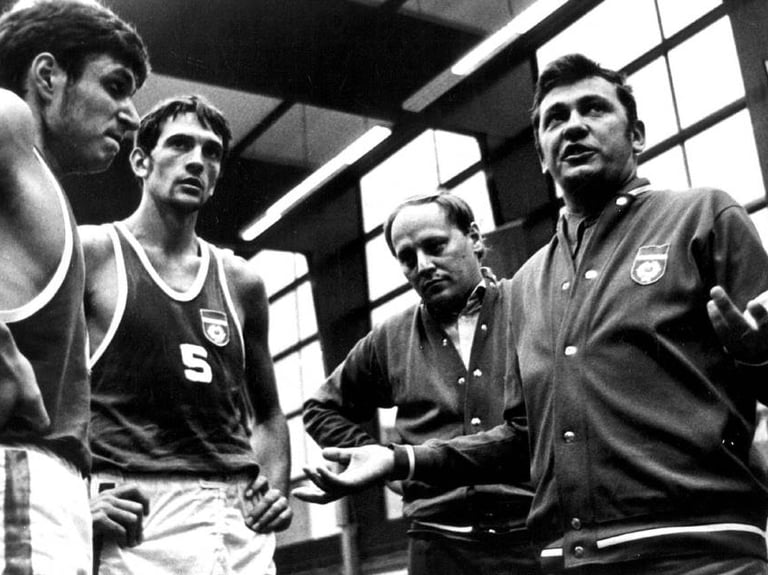

He could now dedicate himself to basketball and Radnički until 1950 when he ended his playing career to fulfill his military duties. Being a smart man, he realized his future lay outside the four lines of the court, which is why in 1951, he accepted to take over the women’s team of the Krstaši, beginning his long journey on the coaching benches. In 1954, he was called to replace Miodrag Stefanović as the head of the men’s team, and through his work, he quickly caught the attention of the “Holy Quartet.” It was Nikolić himself who offered him the position of assistant coach for the Plavi, for it should be remembered that when it came to Yugoslav basketball, everyone worked for the benefit and progress of the national team. Alongside Nikolić, Žeravica won his first medals, silver and bronze, at the EuroBaskets of 1961, 1963, and 1965, and at the 1963 World Championship.

When the “Professor” left for Italy, the succession plan was ready, and Ranko took on the heavy burden. With the goal of the 1970 World Championship in Ljubljana, Žeravica began to bring new faces into the team, including an 18-year-old with delicate movements named Krešimir Ćosić. Žeravica aimed to create an unstoppable duo in the paint, pairing the young Krešo with Radivoj Korać. The silver medal at the 1967 World Championship seemed to vindicate Žeravica, who perhaps became overconfident, and at the EuroBasket later that year in Helsinki, he took five 19-year-olds, leaving out veterans like Daneu and Korać, looking to the future and throwing Yugoslavia’s future stars -Simonović, Kapisodi, and Ćosić- into the deep end. The Plavi’s collapse into ninth place caused turmoil, but once again, Nikolić and the “Holy Quartet” acted as a shield, allowing Žeravica to continue his work undisturbed. And wisely, with a blend of experience and youth, he took two consecutive second places in 1968 and 1969 (Olympics and EuroBasket) while awaiting the 1970 World Championship with anticipation.

But death was lurking that summer day on a provincial road outside Sarajevo. The night before, the national team had played a friendly against a Bosnian Herzegovina select team, and on June 2, 1969, Žeravica was driving towards Belgrade with his wife as a passenger. Behind them, Korać was driving his Volkswagen 1200, attempting to overtake a vehicle ahead without clear visibility. Žeravica saw in horror in his rear-view mirror the violent collision of the Volkswagen with a bus coming from the opposite direction and was the first to run to the accident site. With the help of bus passengers, he placed the injured Korać in his car, and while frantically driving to the hospital, Radivoj Korać died in the back seat in the arms of Žaga Žeravica. All of Yugoslavia mourned Korać’s tragic death, including his national teammates, who now had to find the strength to stand tall and play for him at the World Championship.

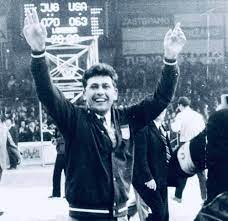

Žeravica managed to lift the devastated spirits of the Plavi, and on May 23, 1970, at Hala Tivoli in Ljubljana, 5,000 Yugoslavs celebrated their champions. It was a triumph and a personal vindication for Ranko, who, besides Korać’s absence, also faced the regime’s suspicion due to his father’s past. Just weeks before the tournament, he had a conversation with Tito’s right-hand man, Stane Dolanc. The second-in-command asked him if he was a party member, a question he obviously knew the answer to. Žeravica avoided the trap, responding with a tone that left no room for misinterpretation by the head of Yugoslavia’s secret services:

“Tell me, do you want the most agreeable coach to you or the most suitable?”

And with that, the conversation ended.

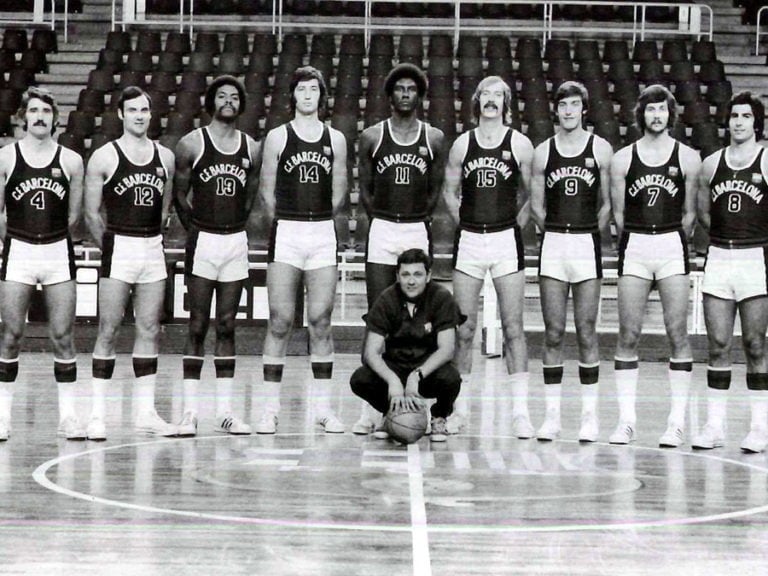

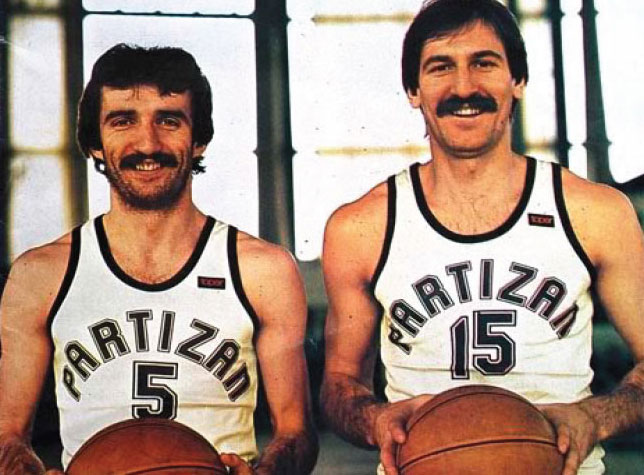

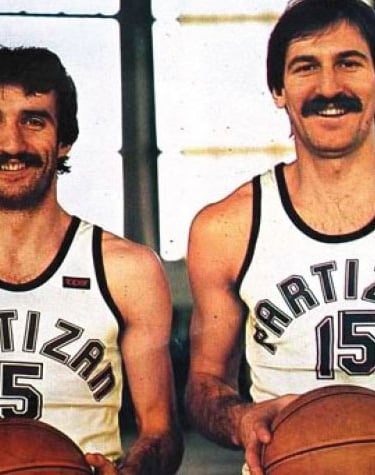

Two years after Ljubljana, Žeravica resigned from the position of national team head coach and began, for the first time, to consider working abroad. However, he did not leave before 1974, simultaneously coaching Partizan since 1971 in his preferred style, promoting and working with young players like Dalipagić and Kićanović. He did the same at Barcelona in his first venture outside Yugoslavia, where he advocated for including San Epifanio in the men’s team during his tenure. When he returned to Partizan in 1976, “Praja” and “Kića” had matured, and Ranko showcased the “deadliest” duo in the European courts, averaging a staggering 110 points per game!!! the Crno Beli won the 1978 Korać Cup but lost the domestic title, despite having the league’s top two scorers (Dalipagić and Kićanović). After a two-year break as a technical advisor in Pula, he once again took the helm of the Plavi, leading them to Olympic gold in Moscow and bronze at the World Championship in Colombia, while simultaneously coaching Partizan’s rival, Crvena Zvezda, until 1986, giving their first chances to Bane Prelević and Boban Janković.

By then, his students were emerging in Yugoslav basketball, with names like Šakota, Đurović, Pešić, and Maljković standing out, while their mentor traveled again to his beloved Spain to coach Zaragoza, followed by a four-year stint in Italy, coaching the remnants of Jugoplastika under the name Slobodna Dalmacija, and finally winning a championship with Partizan in 1996. When he retired from coaching in 2003, he split his time between Belgrade and Zaragoza, where he had purchased a home. In 2009, he suffered his first heart attack there, which was not fatal but left him with severe health issues, leading to a second heart attack that resulted in his death in Belgrade on October 29, 2015.

Žeravica left this life doing what he loved, watching a basketball game on television shortly before his death. He went to meet Nikolić, to argue one last time about whether to play control basketball or let the team run, whether a coach should be liked or feared by the players, and to agree that the young player should have the ball in his hands when it matters most. He was buried in the Garden of Distinguished Citizens, near his beloved “child,” Radivoj Korać. At his funeral, players and coaches, now split into Serbs and Croats, Bosnians and Slovenes but all Yugoslavs in the years of triumph, came to honor their teacher. There were Skansi and Solman, Tanjević with Plećaš and Novosel, Maljković, Bodiroga, Danilović, Dalipagić, Slavnić, Kićanović with Radovanović just to name a few.

The final roll call, the last national team of Ranko...