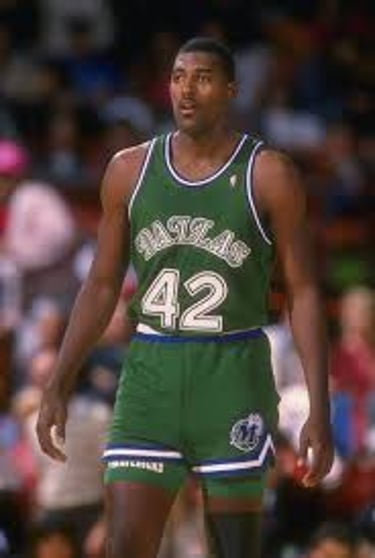

Roy Tarpley

"Tarp the Shark”

RETROPLAYERS

Antreas Tsemperlidis

12/3/20259 min read

He felt his head heavy. The headache was as if someone had put it in a vise and was squeezing until his eyes were ready to pop out. His mouth was drier than the desert. The darkness around him didn’t help him figure out where he was.

He tried to get up from the bed and stepped on something with his bare foot that startled him. He bent down to pick it up and immediately realized what it was. An empty beer can — a remnant of the night’s debauchery.

He walked to the window and yanked the curtains open. The sunlight blinded him, but like a flash in his mind everything became clear.

He, Roy Tarpley, was in Tel Aviv with Olympiacos and that night he would be fighting for the European Championship trophy. He got dressed quickly and went down to the hotel lobby. His teammates greeted him, except for Babis Papadakis, who looked at him fearfully. He paid no attention and quickly walked toward Xanthos. “Good morning, coach,” he said with a smile.

Ioannidis looked at him and muttered through his teeth. He didn’t want to add fuel to the fire before such an important game. Let him win the Champions Cup first; there would be time for remarks later. Besides, the safety clauses in Roy’s contract covered everything, and with Tarpley’s past, one might say they were too few. But without that past on his back, “Tarp the Shark” would never have crossed the Atlantic.

For what reason anyway? In a basketball utopia his career would have been predetermined: one of the best NCAA players, high draft pick by an excellent team, stellar NBA performances, future superstar, perhaps a championship, and why not, eventual entry into the Hall of Fame. But as we said… all that in an ideal world. In the real one — where actions have consequences — Roy Tarpley, up to 1986, had managed to confirm every good thing written and said about him.

In the four years he played for Michigan’s “Wolverines,” he managed to win Big Ten Player of the Year in 1985, set the school record with 11 blocks in a single game, and finish his college career as the university’s all-time blocks leader. His performance could not go unnoticed, and comparisons with Bob McAdoo had already begun.

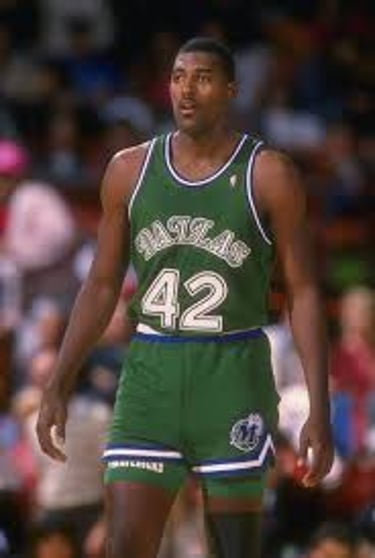

Regarding the infamous — for all the wrong reasons — “cursed” 1986 draft, I’ve written before in other features about the players involved. If a historian of the future could warn the first seven teams about the fate of their picks, perhaps they would think twice. But since that wasn’t possible, the Dallas Mavericks celebrated that the other six organizations didn’t select Roy, allowing them to “snatch” him at seventh.

The Mavs of that era were a strong team, with All-Stars like Blackman and Aguirre and excellent supporting players such as Schrempf, Derek Harper, and Sam Perkins.

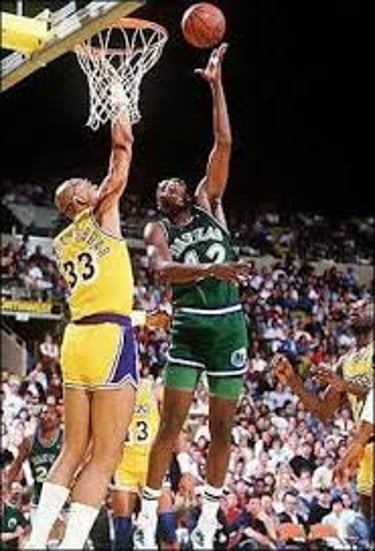

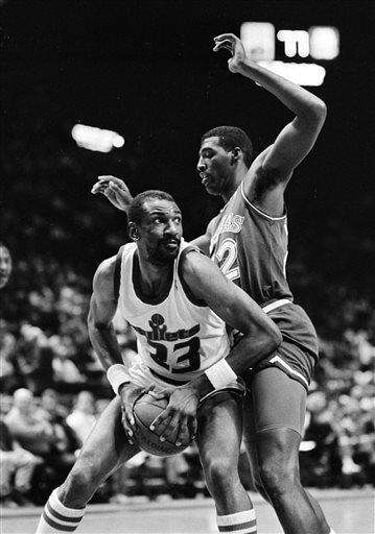

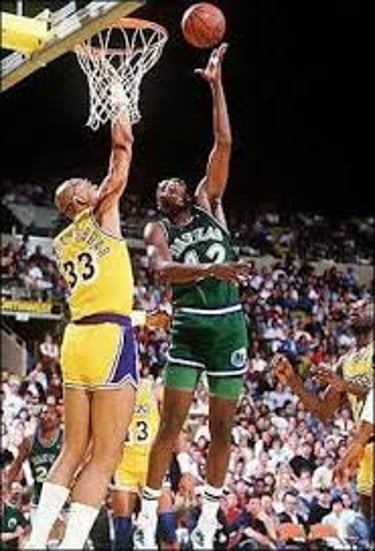

Tarpley fit perfectly into Dick Motta’s team and by season’s end was rewarded with a spot on the NBA All-Rookie First Team. The 1987–88 season was the one that established Roy as one of the NBA’s top big men — and simultaneously the last complete sample of his enormous talent. Coming off the bench as a power forward, Tarp would claim the Sixth Man of the Year Award and help Dallas reach an epic Western Conference Finals series against the eventual champions, the Lakers.

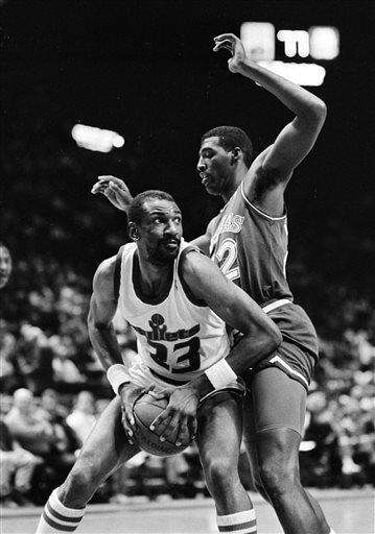

Roy did incredible things in those games. Despite being 2.11 meters tall, he ran the court like a deer, shot like a perimeter player, grabbed rebounds like peanuts, and looked unstoppable by Worthy and Green.

And while his career seemed destined for glory, he kicked everything he had built during those two years in the NBA. In a league where in the ’80s about 90% of players smoked marijuana and quite a few used hard drugs, the Mavericks’ staff likely weren’t shocked when they realized Roy had fallen into addiction to alcohol and cocaine. They mobilized immediately, wanting to save his life first, his career second, and, naturally, protect their investment.

Tarpley entered rehab, attended weekly sessions, and was constantly monitored by a specialist. A few days before Christmas 1988 the supervisor grew worried when Roy stopped answering his calls. He rushed to his home and, searching the trash, found countless empty beer cans — then inside found Roy submerged in a sea of cocaine. The NBA came down hard. On January 5, 1989 his suspension for the remainder of the season was announced. It was the beginning of the end for his NBA career.

He returned in 1989–90 but, with the specter of drugs looming, played only 45 games — oddly with very good stats. When he was sober and clean, he resembled the player Americans compared to Olajuwon. Tarpley began 1990 furiously, determined to show a new face. Until that November night in Orlando. Near the end of the first quarter he collapsed with excruciating pain in his right knee. The diagnosis — a complete ACL tear — was devastating, and for someone with Roy’s problems, it was the final straw. With his spirits in ruins, it was only a matter of time before he relapsed.

On October 17, 1991 Tarpley was banned from the NBA for life after failing a third consecutive drug test. As if that weren’t enough, there were allegations of violence — during a rage episode he “ironed” his then-girlfriend. Rehabilitation followed again, this time at John Lucas’s recovery center in Florida. There, under the guidance of the also-recovering coach, Roy found peace for the first time. Perhaps that was why, after graduating from the program and since he was above all a professional basketball player, the team that trusted him was Lucas’s Miami Tropics of the semi-pro USBL. He needed money anyway, and as he himself said, “Basketball is the same everywhere — they just pay better in the NBA.”

Money was Tarpley’s big motivation — and since the NBA was now persona non grata, he would go wherever the pay was highest, even if that meant the other side of the world.

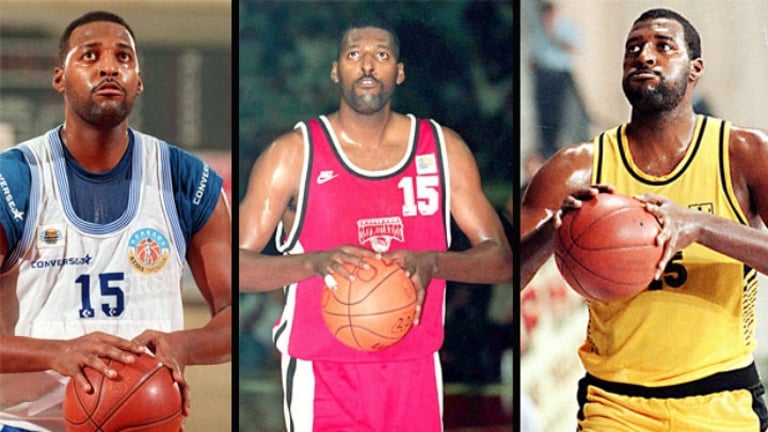

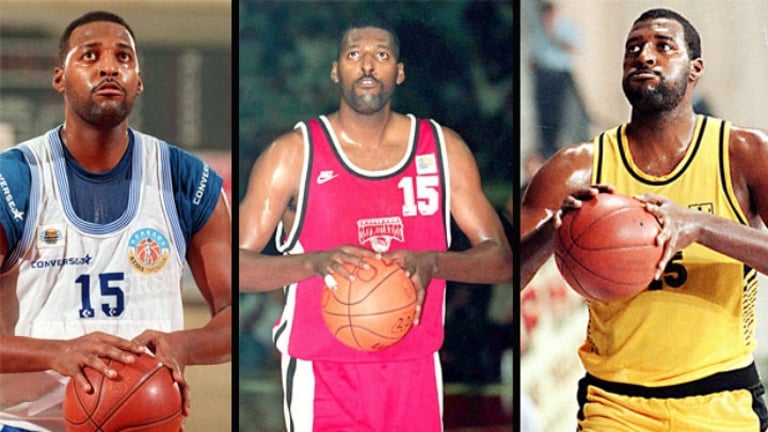

In the summer of 1992 in Thessaloniki, Theofilos Mitroudis was trying to keep the Aris organization from collapsing after the shock of Nikos Galis’s expulsion. His ally in this mission was the new coach, Steve Giatzoglou. The two sought a player who could calm the fans’ anger and strengthen the team.

The excellent connoisseur of the U.S. market, Steve, suggested Tarpley’s name. Mitroudis was hesitant and wondered if such a player would come to Greece. Giatzoglou reassured him: “President, this guy pissed away six million — he’ll stick with us.” And indeed, Roy didn’t hesitate and arrived in Thessaloniki ready to lead the new Aris.

The fans were searching for a new idol — and Tarp was exactly that. When the official games started, everyone believed they had found the man who would bring them the championship again, especially after the derby of the second round against PAOK, where he made Fasoulas and Livingston look like children. Wearing the Aris jersey, he dominated the first half of the season, terrorizing opponents. Playing with immense confidence and superb technical skill, he was a bulldozer.

As long as he stayed away from alcohol — at least by his standards — the “Emperor” marched triumphantly in Greece and Europe. But fairy tales don’t come without a dragon.

Mid-season, Tarpley was injured, and the then-leaders Aris slipped to 5th place while waiting for his return, losing home-court advantage for the playoffs. Roy came back after nearly two months and joined Svi Serf’s squad, who had replaced Giatzoglou. Aris had a huge chance at a European trophy and feared nothing with Tarpley on the roster. In Turin he dominated Efes’s big men and won the Cup Winners’ Cup. Around the same time but elsewhere, Zarko Paspalj stepped(?) on the line in Boblan and Olympiacos suffered a traumatic elimination. The two teams met in Chalkida for the first playoff game due to Olympiacos’s ban.

Roy’s poor performance and the loss fueled the rumors that a hotel employee found 35 empty beer cans in his room. Newspapers ran four-column stories, Mitroudis was late with salaries, and Roy, feeling uncomfortable at Aris, one morning packed his bags and fled for America, abandoning the team before the league and Cup finals.

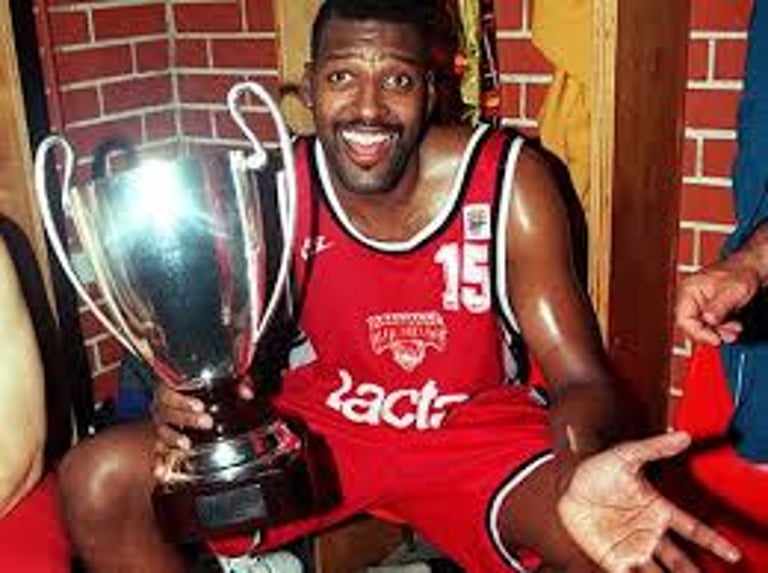

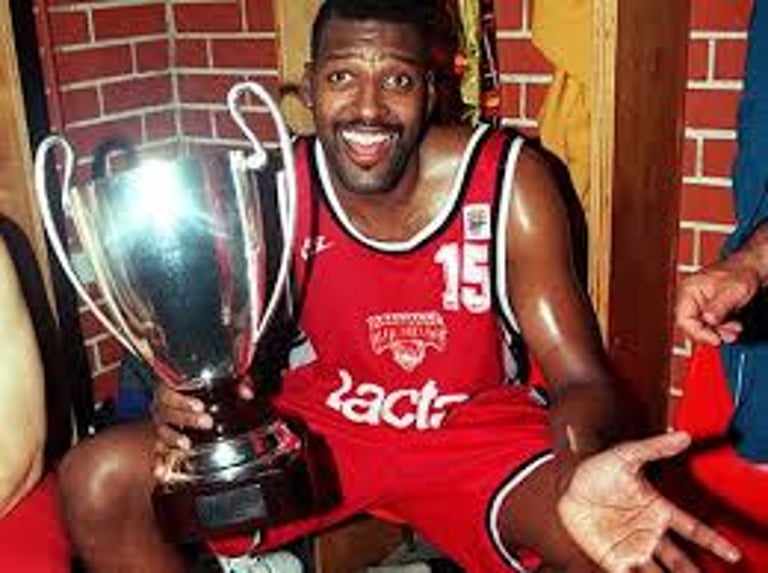

In Greece most believed he had left for good — but they hadn’t counted on Giorgos Salonikis, who had almost coup-like secured Tarpley’s signature as Berry’s replacement. Olympiacos now had Europe’s strongest front line, and their fans dreamed of the Champions Cup.

Roy adapted quickly, becoming a perfect cog in Ioannidis’s well-oiled machine, doing everything on the court — even if sometimes he made Xanthos lose his temper.

Olympiacos arrived in Tel Aviv as favorites. Ioannidis isolated the team in a remote hotel to prepare for the semifinal. Tarpley was the team’s best player in the “civil war” against Panathinaikos, and while everyone was celebrating the qualification in the locker room, he decided to show his old “good” self.

He remembered that earlier that season, after a loss, Ioannidis had asked players to point out who they believed wasn’t earning his salary. Babis Papadakis had made the mistake of saying one of them was Tarpley.

Roy hadn’t forgotten — and chose that moment of joy to turn the locker room into a rodeo and beat his unlucky teammate. After they were separated, a monumental fight with the coach followed, and Roy locked himself in his room with the only thing that could calm him.

With Kokkalis’s intervention, calm seemingly returned, but on April 21, 1994 Tarpley dragged himself on the court and Olympiacos played tragically, leaving with heads down. The league title was the only salvation, and Tarp put his stamp on it. First in the regular-season derby against Panathinaikos that decided first place, he took initiative and hit two out-of-system threes to win the game. Then in the finals against PAOK he dominated Berry and Savic. Days later he completed the double by winning the Cup final against Iraklis. Thus Roy left Greece for a second time — this time with good memories.

Before the 1995–96 season, during a breathalyzer test, his levels went off the charts. The league, waiting for players with Roy’s past to slip, was relentless. Permanent NBA ban with no right to appeal. Tarpley protested, claiming they were just looking for an excuse — but found no supporters, not even within his team. In November 1995, while hospitalized with a serious pancreatic issue, the Mavericks terminated his contract without compensation. Thus ended the NBA chapter of Roy’s turbulent life. The Greece chapter, however, had a few pages left.

Iraklis was his next destination, and in the country that loved him and forgave his sins, he once again showed his good side. With “Girondis” he even reached a Cup final, losing to Panathinaikos. It was the last season Tarpley showed even glimpses of his undeniable talent. The following years he dragged his battered body anywhere in the world where teams were willing to offer him a few thousand dollars — enough to pay his enormous debts and survive. Cyprus, Russia, China, and back to Greece with Esperos — older, heavier by some 30 kilos, a ghost of himself. His downfall was endless, and he even saw the inside of a prison cell. In 2002 he declared bankruptcy due to overwhelming debt. The man who had signed million-dollar contracts had reached the point of living on ten dollars a week, sinking in an ocean of alcohol. But he wanted to leave the game he belonged to with his head held high — because he wanted to, not because he was forced out. In 2003, at age 39, he asked the NBA to allow him even a 10-day contract so he could say goodbye proudly. Believing he had no chance, officials demanded that he pass drug tests for an entire year. Astonished, they watched him remain clean every week. Thrilled, he formally requested reinstatement — but in October 2005 the league denied his request without explanation. They simply rejected him, unjustifiably in his view.

So in 2006, invoking an equal-employment clause, he sued the NBA and the Mavericks, claiming he was a person with a disability. He sought $6 million, and the case settled in 2009 — rumors say he received mere crumbs, a little over $50,000. It was the last time Roy’s name was heard in relation to basketball. The next time would be for the worst reason. On January 9, 2015 his liver and other exhausted organs failed due to years of abuse. He was only 50, and alcohol must have replaced the blood in his veins.

Roy left — perhaps to a place where he could freely chug down a whole crate of beer. Because he never managed to defeat himself. Maybe because God, seeing how much talent he gave him, sent a demon to torture him and keep balance. Or maybe that demon was the one the Ancient Greeks meant — the conscience. That’s how Tarpley lived his life…

Following his inner demon, acting as his conscience dictated, wanting to live and die in his own self-destructive way.

Bottoms up, great Roy…