Stojan Vranković

A nasty "Tree"

RETROPLAYERS

Antreas Tsemperlidis

3/25/202510 min read

The worn-out and dusty YUGO parked in the open area of the Drnis stadium. Its driver got out and briskly walked toward the entrance. Even if he had closed his eyes at that moment, the sound of the ball bouncing on the parquet could have guided him. He hoped his information was correct and that the 50 km he had travelled between the two cities wasn’t in vain. He didn’t have much time, as he needed to return to Šibenik by the same afternoon.

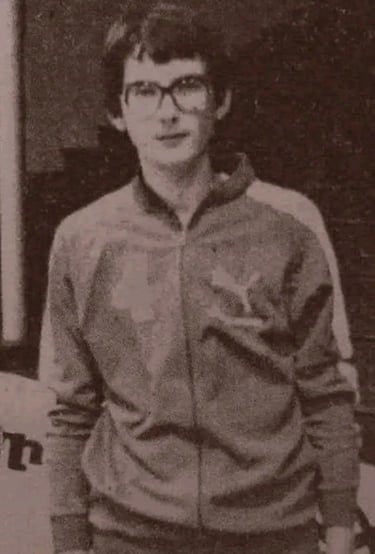

The kid with the messy hair and sparkling eyes he had come for loved training and considered his day wasted if he didn’t give his all on the court. A colleague was giving instructions to a group of children, among whom the 14-year-old with large myopic glasses stood out. At 2.03 meters tall, Stojan Vranković towered over all his teammates, but at that time, his height was his only asset. At least that was the opinion of those in charge, which they conveyed to Nino Jelavić, the coach of Šibenka's youth team, who had come to the court to see the young player in action. The experienced Jelavić turned a deaf ear to their discouraging remarks and, after a brief discussion with the boy's family, convinced Stojan to follow him to Šibenik. The Yugoslav coach was considered the best youth trainer in his country and aimed, through hard work, to transform the raw Vranković into an excellent basketball player. In his mind, he was already envisioning a collaboration between Vranković and Dražen Petrović. However, the plans of Šibenka’s "big wigs" didn’t include Stojko. The final assessment of the bespectacled Vranković was that he "didn’t fit." Jelavić tried his best to convince management they were wrong, but he hit a wall.

However, he didn’t abandon the shy young man he had taken under his wing. Using his connections, he took Vranković to Zadar, where the young player joined the team in 1980. So Stojan left Šibenik with the friendship of the arrogant Petrović in his bags, who in turn had already debuted in the domestic league and was already –justifiably- being groomed as the next big star of Yugoslav sports.

In 1987, Stojan experienced a year of missed opportunities, beginning with Zadar reaching the final six of the European Champions Cup but failing to secure a spot in the Lausanne final. In the domestic league, Partizan seized the crown after eliminating the Croatians in the quarterfinals. During the summer in Athens, he witnessed Greece's Eurobasket triumph which marked his first close interaction with Panagiotis Fasoulas, the first of many in the years to come.

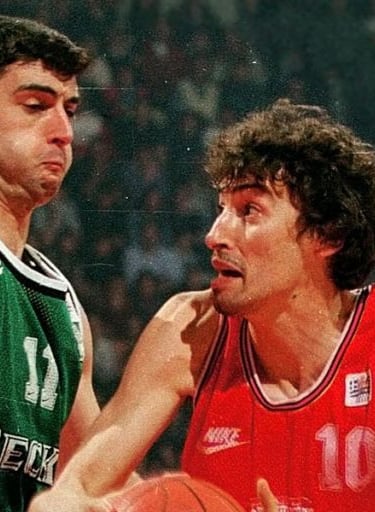

Another medal, this time a silver, was added to his collection at the 1988 Olympics in Korea. During the Christmas International Cup in Madrid later that year, rumors of a transfer abroad began to surface. Despite Real Madrid's rumoured interest, no official offer materialized. In the summer of 1989, European champion Stojan prepared for the next chapter of his career. Unlike Real, Aris, desperate to win the European trophy, offered a $200,000 contract. Ioannidis consulted Galis about the Yugoslav player, and Galis remarked, "Coach, he's the only one who makes it so hard for me. When I go near the basket, it’s like facing a tree with all its branches spread out." At 25, Vrankovic played a decisive role in leading the Greek "Emperor" to Zaragoza with arguably the best team in the team’s history and sky-high expectations. However, a harsh semifinal loss to Barcelona gored Aris's and Greek basketball’s dreams, exposing issues that had been carefully hidden. Stojan missed the third-place match against Limoges due to an official back injury, though unofficially this was linked to financial disputes with management. Eventually, president Michaillidis resolved the arrears, and Vrankovic returned to help Aris reclaim the Greek championship, overcoming Fasoulas in their aerial duels.

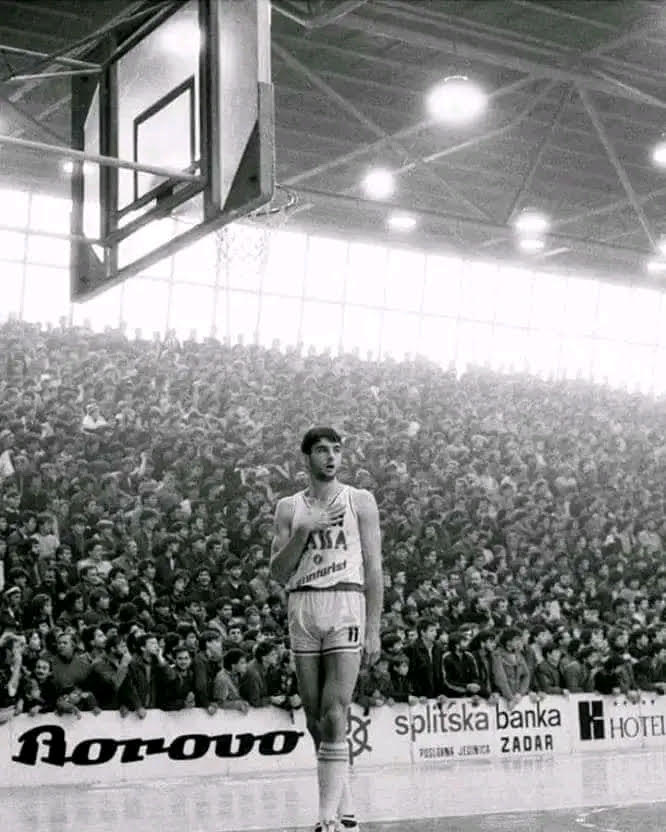

In Zadar, the cradle of Croatian basketball, the Dalmatian -now viewing the world from a height of 2.17 meters- poured rivers of sweat in daily, rigorous training under the supervision of local legend Josip "Pino" Gjergja. And vindication came for Vranković in 1981 when, donning the legendary No. 11 jersey (that of Krešimir Ćosić), he set foot on the iconic herringbone parquet of "Jazine." The qualities that would define his career were evident from the start: an exceptional defender, with long arms and remarkable jumping ability. He could grab rebounds effortlessly and acted as a goalkeeper who didn’t even let a fly get near the basket. However, his offensive limitations were also apparent, as he wasn’t a threat beyond three meters, and his moves were restricted. If he did get the ball near the basket though, he was nearly unstoppable. But in Zadar, with sharpshooter teammates like Branko Skroče and Petar Popović, no one expected Stojko to score. In the highly competitive Yugoslav league of the 1980s, where at least five teams vied for the title, Vranković’s defensive skills were invaluable to his coach. One of them, during his single season coaching the team, decided to utilize him offensively as well. Returning from Germany and the ill-fated EuroBasket 1985 for Yugoslavia, Stojan began preparations under the guidance of Vlade Đurović, the moustachioed moral champion of 1983 with Dražen’s Šibenka. In perhaps the best year of his career, Vranković averaged 20 points per game and achieved some dazzling & unmatched records, like 15 blocks in a game or 36 rebounds in a Korać Cup match against Hapoel Jerusalem. On April 26, 1986, in a packed "Dom Sportova," Zadar pulled off a major upset in the third and decisive finals match by breaking Cibona’s home-court advantage. Stojan was the star player of his team, the hero of the city, and one of the best centers in the league.

Another legendary center, now the coach of the national team, will include him in the squad for the 1986 FIBA World Cup on the Iberian Peninsula. There, Divac's mistake and the execution by Sabonis and Walters will elevate Vranković and Ćosić to the third step of the podium.

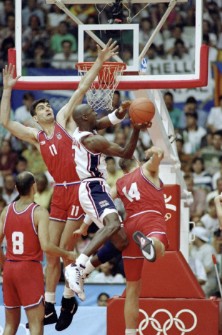

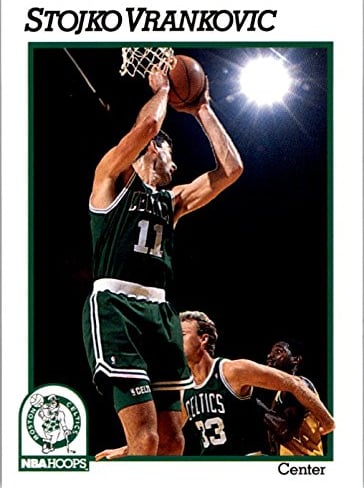

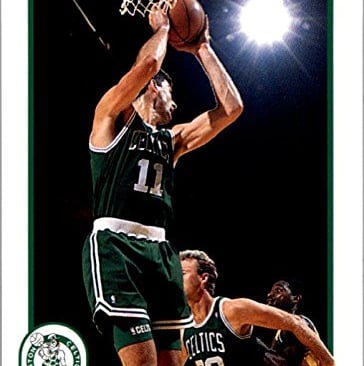

In the summer, Stojan left Thessaloniki and crossed the Atlantic to join the Boston Celtics who, entering a decline, saw him as a promising backup for Robert Parish. Stojan was eager to seize his NBA opportunity, but both sides were ultimately disappointed. Struggling to adapt to the NBA the Yugoslav failed to win the trust of Chris Ford, with his coach arguing that he couldn't understand the different style of play in the NBA. Stojan only got sporadic, limited minutes and earned the nickname "Human Victory Cigar," a nod to Red Auerbach’s celebratory cigars during Boston’s glory days. This inactivity cost him a spot on the national team, depriving him of the chance to claim gold -the last gold medal of the legendary Plavi unified team- at the European Championship in Rome. Instead, he trained individually in Boston, only to earn a prime seat on the Celtics’ bench. After minimal appearances, often noted as "DNP CD" (Did Not Play, Coach Decision), he returned to Europe post-Barcelona Olympics, where he had a small redemption by blocking even Jordan in the final against the Dream Team. With the silver medal, Vrankovic sought his next career step.

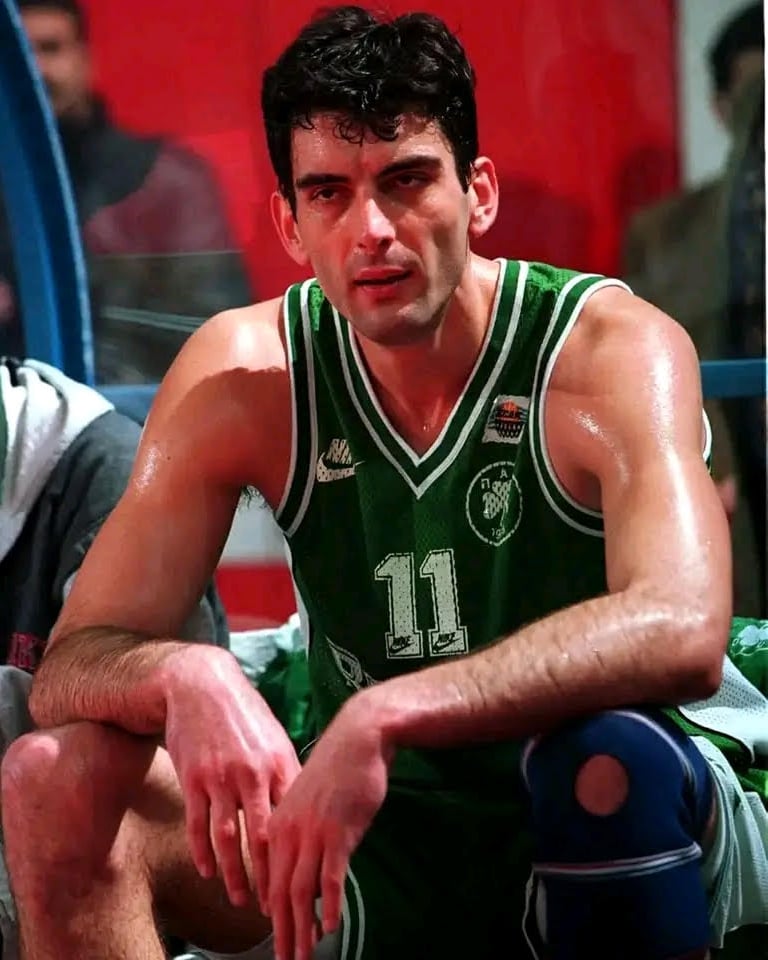

Real Madrid surfaced a potential suitor again, but Greek teams officially entered the race. Olympiacos pursued him, but Panathinaikos ultimately secured his signature in August 1992 with a $1.5 million contract, leveraging the presence of coach "Μr. two cups" Zeljko Pavlicevic and compatriot Arijan Komazec. Vrankovic became Panathinaikos' main center, known for his defensive prowess, with commentators often repeating, "Vrankovic blocks”, "Vrankovic stops him” and "Vrankovic shuts it down." The team had a stellar season led by Galis, but an injury in the finals against Olympiacos sidelined Stojan, impacting their championship bid. Controversies followed, including accusations against referees and a disputed game postponement. Olympiacos ultimately won the title. The year ended successfully for the Greens with the capture of the Cup and their return to the Champions Cup. Vranković left for Poland and Wrocław, where the Challenge Round was held, with the prize being a spot in the European Championship in Germany. In addition to strengthening Croatia, he had taken on another mission. He was trying to convince Dražen Petrović, the "Mozart," to sign with Panathinaikos. The last words they exchanged were at the Frankfurt airport. Stoijan told Dražen not to travel by car but to board the flight to Zagreb with the rest of the team. Petrović’s response –a tragic irony- came with that trademark disarming smile and left no room for discussion: "You fly, you die Stojko." The next time they met, Dražen was lying dead in a coffin, carried by a 2.17-meter-tall human wreckage. The big-man together with his distraught national teammates placed the coffin in the Croatian soil that opened its cold embrace to welcome its beloved child forever. The Croats collected their pieces, fought at the 1993 European Championship, and dedicated the bronze medal to the great absentee. Stoijan returned to Athens and, instead of Dražen, found Sasha Volkov as a replacement for Komazec in Panathinaikos’ attempt to qualify for the Final Four in Tel Aviv and dethrone Olympiakos in the domestic league. The 1993-94 season ended with empty hands for his team in both competitions, and at the World Basketball Championship in Canada, Croatia again fell victim to the Russians in the semifinals, with the bronze medal surely not meeting expectations. Back in Greece, the only constant in the green defence was Vranković. A new partner in the foreign duo, his old friend Zarko, who wanted to prove that he was unfairly expelled by the greens’ ultimate rivals. The opportunity quickly presented itself. The draw pitted the eternal rivals in the first round of the Cup in a knockout match. In a game that, if sports police was an actual thing it would have arrested all the participants for the violent abuse of the sport, Panathinaikos won a depressing 42:40 victory. At that moment, Vranković expressed his emotions, and the fans embraced him into their hearts forever. "Stoijan the madman," as he was called, climbed the fences of the Sporting arena, fell into the arms of his Panathinaikos friends, and became one with them. But the one who smiled last was Olympiakos, first in Zaragoza and then in Faliro, in the third dramatic championship final.

Number three chased Vranković in the European Championship in Athens, with Croatia finishing in the well-known third place, while the Greek national team played the role of the "fool" in yet another tournament. The tournament was scared by the unacceptable act of the Croats leaving the winners' podium while the Serbs were raising the trophy in the sky of OAKA. The order was signed-off by Croatian President Franjo Tuđman and had the full support of the top players of Hrvatska, with Stoijan being the most enthusiastic supporter of this decision. The wounds of the civil war were still very fresh and bloddy. However, on the court, the Dalmatian was a perfect professional, and his collaboration with the new coach from Serbia, who replaced Kiumourtzoglou, proceeded without any problems.

Božidar Maljković was tasked with bringing Panathinaikos to the top of Europe, and the Giannakopoulos family provided him with a "nuclear" weapon. The NBA great Dominique Wilkins arrived as a saviour, but from the start, his relationship with Maljković was problematic. When both eventually compromised, the team found some calm and managed to advance as third in their group to face Benetton Treviso in the quarterfinals. The Italians had home-court advantage. Panathinaikos won narrowly in Athens, lost heavily in the return leg in Treviso, and on March 14, 1996, Željko Rebrača was preparing to take a shot from four meters to give his team the victory and qualification. Vranković’s outstretched hand stopped the Italian dreams, and the ticket to the Final Four in Paris was issued in the name of Panathinaikos instead. In the semifinal with CSKA, the "Dalmatian wall" rose to deny the Russians seven times, Dominique shredded the Russian defence with a 35-point performance, and the 8,000 Panathinaikos fans scheduled their meeting for the big final on April 11 with the "Bull of Catalonia." Let’s fast forward to the last 36" of the game. Giannakis had the ball with a clear intention to attack at the end of the clock, so as not to leave much time for Barcelona. Suddenly, with the suspicion of a foul, he slipped, and the ball found its way to Galilea. While the scoreboard crew was giving a recital of errors, Montero was ready to score and paint the Cup in Blaugrana. In one of the most iconic final moments of European finals basketball history, just as time seemed to stop, the Spaniard suddenly saw a scarecrow covering the basket, blocking the ball against the backboard. As the fans held their breath, Stojan Vranković began a desperate race to save what he could. He covered 25 meters with three strides, almost trampling on poor John Korfas, who was in his way, and became the last moment hero - the man who appeared out of nowhere. He then fell on the court, injured from the overexertion, but got back up a little later to join the celebrations for a trophy that in large part were only taking place due to him.

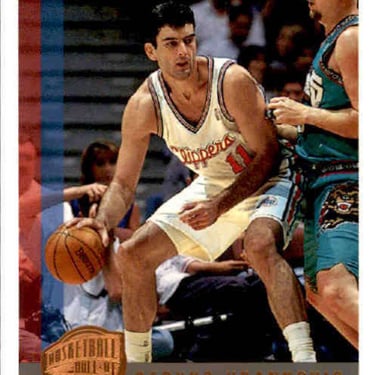

He no longer had anything to prove in Europe, and when the Greek finals were over in losss, he packed his bags and crossed the Rubicon of the NBA once again. This time, the conditions were better with the Minnesota Timberwolves, playing several games as a starter, but his statistics and general presence were again unremarkable. Things didn’t change at his next stop, the cosmopolitan Los Angeles, and the city’s poor relative, the Clippers. The NBA didn’t suit Vranković, and Stojan never fit into any organization. At 35, he returned to European basketball, but not to his beloved Greece, rather to neighbouring Italy. The Spaghetti Circuit and Fortitudo Bologna opened their doors, and in his first season there, Vranković won the championship. In northern Italy, Stojan took his final bow in 2001 at the age of 37.

A legend of European basketball and an absolute icon for Panathinaikos and its fans, Stojan is one of the greatest players in the team's history and according to a 2015 pole the top center to have worn the green shirt. Apart from his tremendous defensive talents, the Croatian was loved for another reason. For his soul and passion. Although he was a foreigner, he never had the characteristics of a mercenary. With Vranković on the court, everyone felt secure, knowing that even if they couldn't defend well, a nasty tree was waiting in the backcourt with all its branches stretched out to cast its long shadow...