Toni Kukoč

"The Spider of Split”

RETROPLAYERS

Antreas Tsemperlidis

11/15/20258 min read

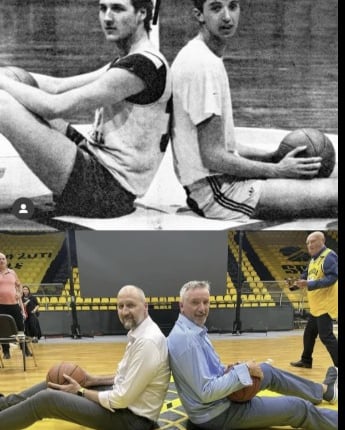

Many believe that sports, even more basketball, are a hidden form of art. If that is true, in my opinion, there is no better representative of this than the poet of the parquet, the most complete basketball player ever to grace the European stage: Toni Kukoč. The achievements of the “Spider of Split” could fill an entire book. Here, I will attempt a brief record of the career of an athlete who marked European basketball history, being part of the two greatest teams ever to appear on the Old Continent at both club and national levels. Let me begin by first expressing gratitude to nature, which blessed “Kuki” with a height unsuitable for ping pong but ideal for basketball. Ping pong, exactly. That was his family’s first choice for him, particularly his mother’s. Radojka Kukoč enrolled him in the sport because the training sessions took place at the “Gripe” gym, just a hundred meters from their family home. Soon, Toni showed great talent, and by the age of just 10, he was the champion of Dalmatia. However, his true love was football, and like every child in Split, his dream was to one day wear the jersey of Hajduk. With his father’s support, Toni passed the tryouts and joined the team’s academy at 11 years old. He was good, but his height would eventually become an obstacle to the goalkeeper career he dreamed of. By 13, he was already 1.90 meters tall but very thin, earning him the nickname “Olive” (after Olive Oyl, Popeye’s girlfriend).

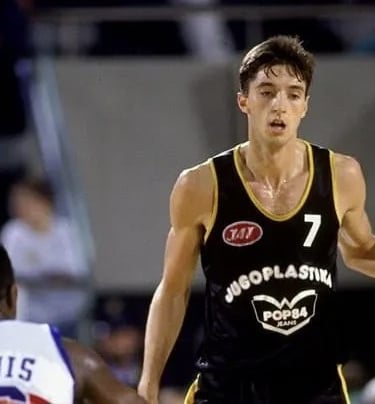

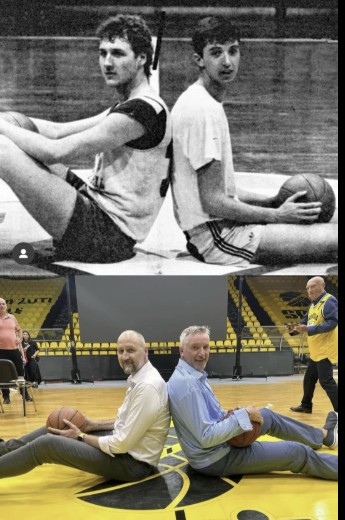

He continued playing football until he was 15, until that summer day in 1983 when a young scout for Jugoplastika named Igor Karković, while walking along the beach, saw a group of young kids playing. What caught his attention was that very tall boy with delicate movements and exceptional coordination. Karković approached Kukoč and was surprised when the young boy told him he had never played basketball before.

He then took the initiative to invite him to the next Jugoplastika practice so the coach could see him, and Toni accepted. It took only a few practices for him to fall in love with the sport and to realize that his future would be colored orange, not black and white.

“When Karković asked me if I wanted to go to Jugoplastika’s practice, I told him I played football. Just once, he said, come to see if you like it. I finally went, and the rest is history”

Toni himself later recalled, and so, he transitioned to the parquet, unveiling his God-given talent.

Split, the city where he was born on September 18, 1968, was known for two reasons: one was Diocletian’s Palace, and the other was its basketball team, a formidable force in the Yugoslav league, KK Split, known to everyone as Jugoplastika. In the 1970s, they were consistently among the top teams, winning titles in 1971 and 1977 and achieving European recognition with two consecutive Korać Cups (1976, 1977). Decline began in the early years of the next decade, leading to relegation in 1981. The “Žuti” (Yellows) returned immediately but with mediocre results until 1986, despite having great Plavi figures like Krešimir Ćosić and Zoran “Moka” Slavnić on the bench. Then came a move that would change history when Aca Nikolić, from his position as technical advisor, handed the team’s keys to a 34-year-old assistant coach from Crvena Zvezda.

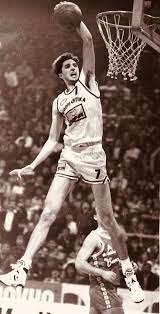

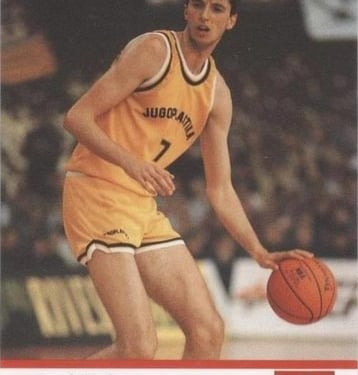

His name was Božidar Maljković. His hiring was followed by the legendary “child-gathering” of Nikolić and Biba Bilić, who promoted or brought in players like Toni, Rađa, Pavićević, Sretenović, and the “platoon mother,” Duško Ivanović. These incredibly talented youngsters would lead Jugoplastika to third place in 1987. The then 18-year-old Kukoč had earned his place as the starting small forward and would rightfully make the roster of the great national team for EuroBasket, earning a bronze medal. His role was limited, but those who saw him that summer in the Peace and Friendship Stadium realized he was destined for greatness. And they wouldn’t have to wait long for confirmation.

The famous “Kukoč Show” at the 1987 FIBA U19 World Championship in Bormio was just the prelude to what was coming. The “babies of Split,” guided by Maljković off the court and the “Pink Panther” on it, managed to overcome the reigning champions Partizan and dethrone them. Thus began the first chapter in the story of the “playground team” that shook Europe.

As champions, Toni went to Korea for the 1988 Olympic Games, returning with a silver medal. There was no time for rest (and truth be told, when you’re 19, you don’t really feel tired), as the 1988-89 season promised to be tough. Jugoplastika entered the European Champions Cup facing all of Europe’s giants. They narrowly advanced to the Final Four with an 8-6 record, traveling to Munich as underdogs since almost no one counted on the “Žuti.” Little did they know… In the semifinals, they grabbed the “Bull of Catalonia” by the horns, and in the final, Maccabi’s titans bowed to the basketball of the next two decades, played by Maljković’s kids.

In Germany, Kukoč demonstrated what an all-around basketball player should be, literally doing everything on the court. He made this even clearer at EuroBasket in Zagreb as a crucial cog in Ivković’s well-oiled machine.

The team that terrorized Europe with its otherworldly basketball did so because it was fortunate to have players like “Kuki” and Rađa, who, at just 20 years old, held the scepters of European basketball, with a bright future ahead. Everyone was waiting to see if the magical season had been a mere firework for Split’s team, and everyone eventually admitted their superiority. In the domestic league, they would break Partizan’s home advantage and win a third consecutive title, with MVP honors going to none other than the man wearing number 7. He was the same man who would deliver another European Champions Cup, this time on Barcelona’s home soil, as the Final Four was held in Zaragoza, Spain. The Catalans wanted revenge for the Munich defeat, but they would once again be left empty-handed. Kukoč, who had toyed with Limoges in the semifinal, was not willing to let go of the trophy. He took his team by the hand—after Dino was quickly burdened with fouls—and using a trick that Obradović would later copy in Bologna (playing point guard on offense, power forward on defense), dismantled every defensive system of Reneses and the referees’ provocative whistles.

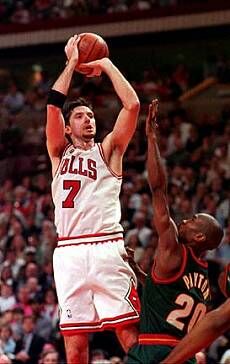

On the parquet of “Principe Felipe,” the “Golden Boy of Split” became a man, and all of Europe bowed to his greatness, realizing that beyond talent, he had character. His star shone in the capital of Aragon, convincing Bulls GM Jerry Krause that he was worth bringing to Chicago. Now officially considered the best European player, he would play with Yugoslavia in the 1990 FIBA World Championship, delivering the best games of his career in the national jersey. The gold medal and MVP award were rewards for his brilliant performances.

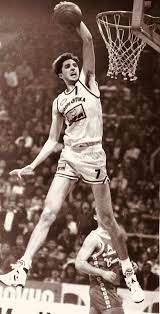

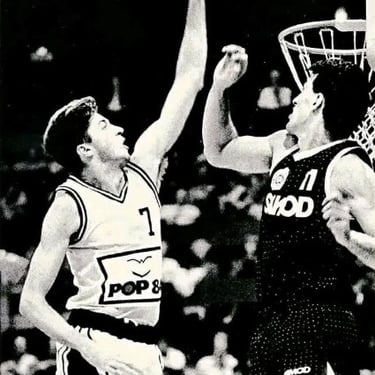

Back in Yugoslavia, however, major changes were taking place. Rađa would say “si” to the millions offered by Raul Gardini and move to Rome, Ivanović became a resident of Spain, and Barcelona, proving the saying “if you can’t beat them, join them,” would give everything to bring Maljković to Catalonia. Even the team’s name changed. Jugoplastika ceased to exist, renamed Pop 84. Kukoč would carry the load for the entire year. In the domestic league, the team was well-structured, and Pavličević gave Toni free rein on the court. The fourth consecutive title was largely thanks to the “Waiter” wearing number 7, but the big challenges would come in Europe.

Everyone was waiting, believing the weakened champions would be easy prey. How wrong they were…

In Paris, they proved they were still hungry for titles, with fire in their eyes. It was a team that wanted everything, gave everything, and conquered everything because its players lived for basketball. Their talent was inversely proportional to their age. For three years, they enchanted Europe because they had ambition, thirst for victory, and love for what they did. What didn’t they have? Fear of their opponents. In every game, they stepped in fearlessly, uncaring if their opponent was Barcelona, Maccabi, or Aris. All they knew was how to win, and that’s what they did at Palais de Bercy.Without Rađa, without Maljković, without the name. So what? In Paris, they reminded us that they were still called Jugoplastika. With Savić “becoming” Dino and the unknown American, A.J. Lester, playing the games of his life, the last champions of united Yugoslavia would write the epic final chapter in their beautiful story.

Nothing would ever be the same after that. This team, which had captivated basketball lovers, would dissolve within months because war does not recognize friendships. The same happened with the national team.

The gold medal at EuroBasket 1991 was already marred by Zdovc’s forced departure. Kukoč was the team’s best player, its leading scorer, and yet another MVP award was added to his collection.

After EuroBasket, Toni would stay in Italy. He would follow his close friend Dino Rađa and sign a royal five-year contract offered by clothing magnate Luciano Benetton. In Treviso, he did what he knew better than anyone else: he led the Italian team to the championship. Coached by his compatriot Petar Skansi and alongside teammates like Vinny Del Negro, Rusconi, and Iacopini, he repaid a portion of the \$13 million Benetton spent to convince him to postpone his NBA dream and wear green. That summer, he would try on yet another jersey, Croatia’s red one. On the parquet of “Pavelló Olímpic,” he would reunite with Rađa, Dražen, and Stojan, and together they would lead Hrvatska to the final against the unbeatable Dream Team. In that game, he would play brilliant basketball, showing his true self. Who knows? Perhaps his basketball ego was wounded on July 27, 1992, the toughest night of his athletic career.

The first match, United States vs. Croatia, was where Kukoč was tortured under the defensive clamps of Pippen and Jordan. Scottie wanted to show Krause, who had “fallen in love” with the Croatian, that all the hype was for nothing, and Michael had no problem backing up his friend since, to them, Kukoč had proven nothing, as the real basketball was only played in the NBA. They alternated in marking him, and Toni got a taste of what awaited him when he decided to take the leap to the other planet. He would delay it only one year, but before doing so, he wanted to leave Europe as a champion. The opportunity came in Athens, in the last Final Four of his career.

PAOK was the clear favorite in the semifinal, but Ragazzi’s shot would “kill” the hopes of the “Two-Headed Eagle” and their dreams of a European title. In the final awaited the surprise of the other semifinal, Limoges, led by Maljković and Zdovc. On the night “basketball died,” in a dreadful final due to the destructive style of the French, an emotional Kukoč would try, with three consecutive three-pointers (and “The Blond Dog” clinging to him), to turn the game around. In the last possession, after switching screens, he found himself facing Forte, who stole the ball, giving victory to the French team. Toni left the court in tears, knowing he would not have another chance; Europe would only see him again as a member of the Croatian national team.

I will not detail “Kuki’s” NBA exploits here—perhaps in another tribute. The player we saw at the 1994 World Championship in Canada, after his first year in Chicago, was different. Not that he wasn’t still an incredible basketball player. Just different. And not just in body…

For me, the lanky kid we first saw in 1987 is the definition of completeness. There was nothing he couldn’t do on the court; he truly was the man of five positions. A Michelangelo of the parquet, who painted the canvas with the ball as his brush, making it all look so simple, so effortless…That is what I will always remember about the artist Toni—the magic of simplicity.