USSR

"Shhh... The “Bear” is sleeping..."

RETROTEAMS

Antreas Tsemperlidis

7/17/20258 min read

Empires rise and fall. They are created, they flourish, they thrive, they dominate, and ultimately, at some point, they decline and collapse like a house of cards. Basketball could not escape this law of nature, and the national team with the largest collection of trophies in history suddenly (or not?) fell into hibernation, which, however, would last forever. But how did we reach 1991 and the failure of the Soviet Union to qualify for EuroBasket in Italy? Who were those, primarily the players and secondarily the coaches (now that I think about it, maybe it wasn’t exactly like that), who led Soviet basketball to the top of Europe and the world?

If we want to start our journey through the paths of history, we must go quite a few years back, almost to the founding of the USSR in 1922. The sport, which had begun to become known in Europe, knocked on the door of the newly established state through the Bulgarians and Hungarians, but initially, it did not meet with much response, at least in the largest of the Republics, “Mother” Russia. In a country that was still trying to establish a new political regime, coming out of a bloody World War followed by an equally dramatic civil war, basketball was certainly not a priority; the primary goal was survival. Yet, even under these difficult conditions, the first championship was organized, and the Moscow team was recorded as the first champion in 1924. In the following years, championships were not held annually, but whenever they were, the teams from Moscow and Leningrad would alternately win the top spot.

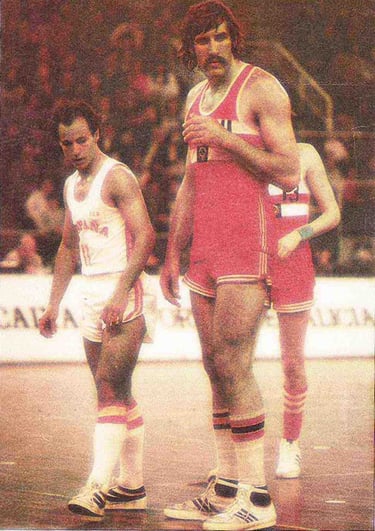

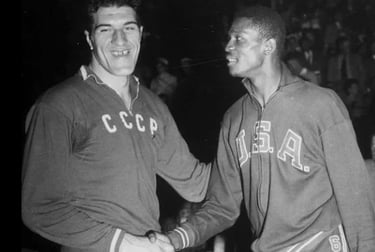

Of course, there was no talk of participation in international competitions like EuroBasket or the Olympic Games. After all, until the outbreak of World War II, there was no national team, and the only sparks could be considered the championships of the “brother” countries Latvia and Lithuania at the EuroBaskets of 1935, 1937, and 1939. The scourge of war abruptly halted the development of the sport, and while the natural progression would have been for the Soviets to appear on the international stage cautiously, they, now as a team, reinforced with players like the first great native Lithuanian basketball player (the Lithuanian star of the pre-war EuroBaskets Pranas Lubinas was born in America as Frank Lubin), Stepas Butautas, the Georgian Otar Korkia, and the tournament MVP Joann Losossof, easily won the European Championship in 1947, opening the cycle of their absolute dominance on the Old Continent. Except for the incomplete Cairo EuroBasket in 1949, from 1951 to 1989, a podium finish (mostly the 1st place) was reserved for the Soviets. With coach Spandaryan and occasionally Konstantin Travin, the “Bear” would win two gold medals in 1951 and 1953 and would emerge as the Americans’ main rival in the Olympic Games. However, they would miss the chance to win a medal in their first participation in a World Championship in 1959 when Moscow decided to withdraw from the tournament due to Taiwan’s participation. In the Soviet Union, nothing happened without the approval of the Commissar, and since the system was deemed successful, no one had the option to refuse. Thus, their great stars like the 2.20m giant Janis Krumins, Alexander Petrov, and Viktor Zubkov were “restricted” to EuroBasket victories from 1957 to 1963 and to silver medals in three consecutive Olympic Games

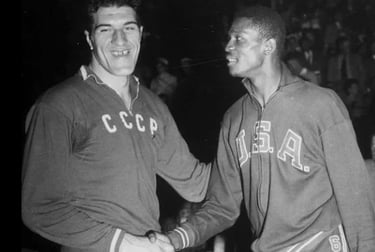

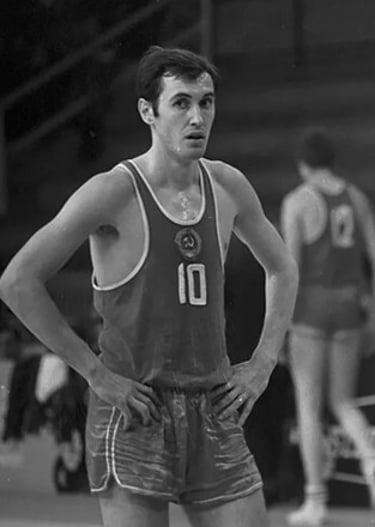

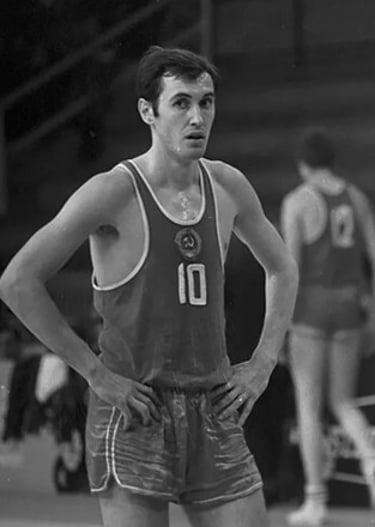

At the helm during all these successes was a bespectacled young man of Jewish descent who would pull the strings behind and in front of the scenes for four decades. His name was Alexander Yakovlevich Gomelsky, and by 1958, he had already made his mark by winning three consecutive newly established European Champions Cups with ASK Riga. Until 1963, the competition was essentially a one-team show, with Dynamo Tbilisi and CSKA succeeding Riga, and Soviet basketball being considered, and truly being, unbeatable up to that point. In the 1960s, some of the greatest players the sport ever produced rose to the stage, with Sergei Belov standing out. Alongside him were namesakes (without any relation) like Alexander Belov, Modestas Paulauskas, and Gennady Volnov. Medals came in a torrent, and by 1971, the tally read ten EuroBasket golds, first place at the 1967 World Cup, plus two bronzes and five silver medals at the Olympic Games. And so, we reached Munich and the most controversial game in basketball history. Without Gomelsky, who “paid” for the regime’s suspicion of defection to the capitalist West, and with Vladimir Kondrashin on the bench, on September 9, 1972, at the Olympiahalle court, it was not just two national teams facing each other but two worlds.

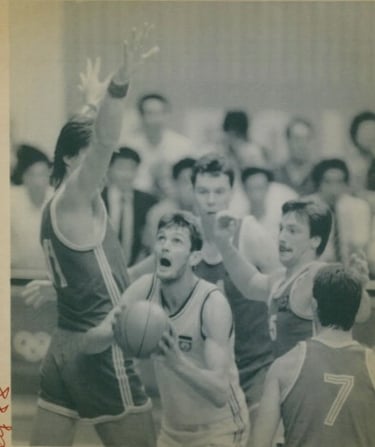

Thousands of words have been written about that game, and tons of ink have been spilled trying to describe its conditions. We all know the story and what transpired during the match with the intervention of FIBA President William Jones, the infamous three seconds, Alexander Belov’s buzzer-beating basket, the Soviets’ celebrations, and the Americans’ refusal to accept their medals. When the ball left the hands of the former javelin thrower Ivan Edeshko with a baseball pass and reached Belov’s hands, adrenaline was through the roof. And when it went through the net, everyone knew the sport would never be the same again. After 63 consecutive victories, the Americans had been dethroned, and the whims of history wanted it to be by their greatest rivals on every level. The “Yankees” protested fiercely but in vain, and Soviet basketball continued its path to success.

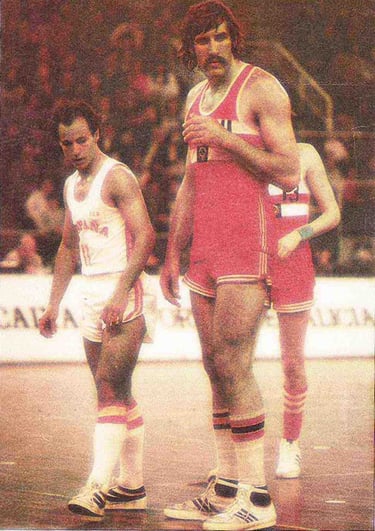

Paradoxically, and because life goes in circles, the Munich triumphants would soon see the other side of the coin. In 1973, in Spain, Diaz’s hosts were not as hospitable, and in the EuroBasket semi-final, they defeated the Soviets of Belov and Myshkin. After eight consecutive golds, the bronze medal surely did not satisfy their ambitions and expectations. The response was immediate, and in 1974 at the World Cup in Puerto Rico, the hammer-and-sickle flag once again flew at the highest pole. That decade was marked by major clashes with the rising power, Yugoslavia, and their hard-fought games. They exchanged the top of the world in 1978, trailed them in the European Championships of 1975 and 1977, and also in the 1976 Olympics.

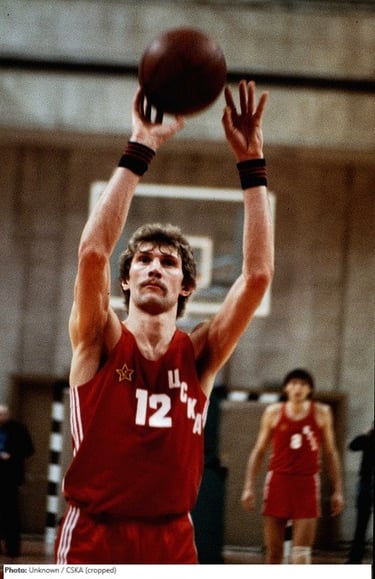

Gomelsky, who in 1971, although absent from the final, won the last Champions Cup with CSKA, had returned to the forefront and was introducing new players, especially among the big men, with the “twin towers” of Tkachenko and Belostenny standing out. In the backcourt, reinforcement was also evident, with Eremin and Khomicius joining the 35-year-old Sergei Belov. With the badge of returning to the top at EuroBasket 1979, first place at the Moscow 1980 Olympic Games was non-negotiable for the Soviets. They were playing at home, the team was excellent, and the Americans were absent due to the boycott. But surprises are inherent in the Olympic tournament, and this time they wore the blue jersey of the Azzurri. Italy, under Gamba, contained Belov with Sacchetti, sending him to play in the consolation final at the end of his great career.

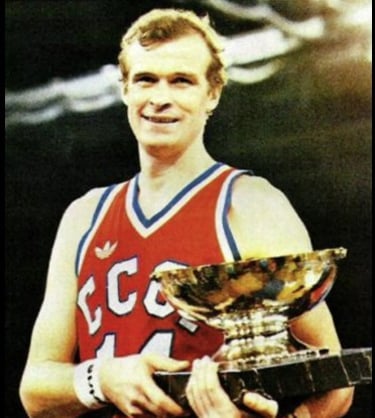

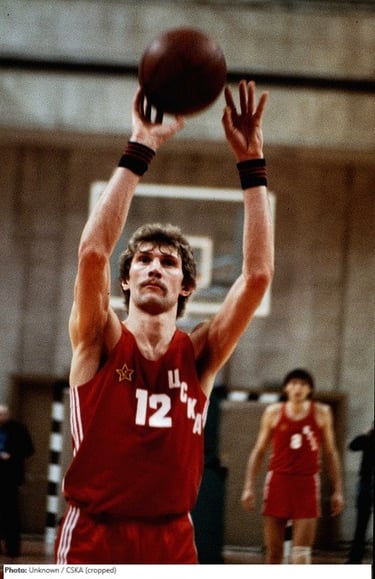

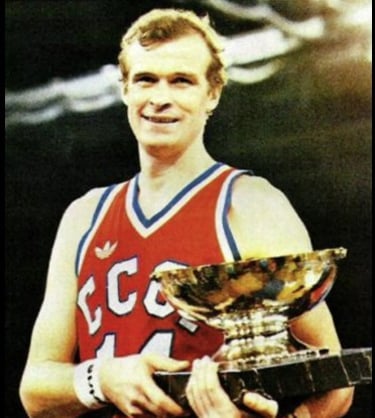

However, the Soviet Union and victory were almost synonymous concepts and could not remain apart for long. With a new leader, Valdis Valters, and Gomelsky always on the bench, they presented at the 1981 European Championship in Czechoslovakia one of the most complete teams, comfortably winning another European title. The champions traveled to Colombia in 1982 with a front line that inspired fear. Myshkin, Tkachenko, and Belostenny dominated the paint. However, the player who amazed and stunned the global basketball community was an 18-year-old who understood the game with the insight of a guard, despite seeing the world from 2.20 meters. Arvydas Sabonis introduced himself that summer in Cali, and everyone realized this player was unlike any who had worn the “Bear’s” jersey before. Until 1986 and his serious injury, Arvydas dominated the courts. In 1983 in France, he overwhelmed his opponents, but in a déjà vu of 1973, the Spaniards knocked him out of the grand final. Gomelsky had two years ahead to prepare the team for EuroBasket in Stuttgart, where he would present a new generation of players, the last of the Soviet system. Volkov, Tikhonenko, and Kurtinaitis found their roles and wore the last gold at a European Championship on their chests.

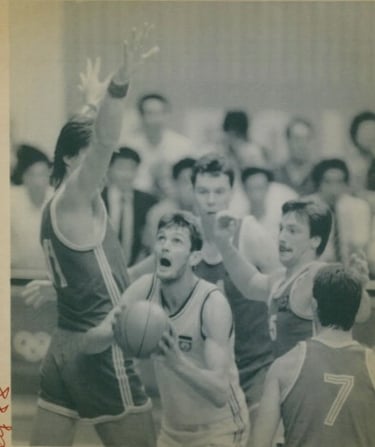

In Madrid in 1986, it took the moves of the young Vlade Divac, the three-pointers from Arvydas, and the “last-minute man” Valdis Valters to beat Yugoslavia in the semi-final and advance to the final, where the Americans got a symbolic revenge for Munich. Valters tried to strike again in Athens, alongside the last great star, Sarunas Marciulionis. Without the injured Sabonis, Gomelsky reached another final, only to fall victim to the phenomenal Greek team.

The visibly unprepared Arvydas was rushed back by the “Colonel” for the Seoul Olympics, and he justified the decision by dominating Robinson and the Yugoslav big men, thus granting Gomelsky an honorary retirement from the national team bench that was never truly final. This was evident at EuroBasket in Zagreb when he used his 12-year-old son Kirill as a “carrier pigeon” to relay his instructions from the stands to the bench where Vladas Garastas sat. Even so, Galis was unstoppable, Fanis hit from 6.25, and the Soviets closed their EuroBasket chapter not with the usual gold, but with bronze.

In 1989, we can say the epilogue for Soviet basketball as we knew it was written. It was the last team staffed with players from all the USSR republics. Communism was on its last legs, and voices of independence began to grow louder. At the World Cup in Argentina, the Lithuanian athletes, who formed the elite and backbone of the national team, refused to participate. The jersey, however, was heavy, and the silver medal was very satisfying for the undermanned Soviets. The last chapter of the most successful national team in Europe was written by Volkov, Tikhonenko, and Bazarevich with Sok and Belostenny. Without them, the Soviet Union (or what was left of it) entered the battle of the qualifiers for EuroBasket 1991. The results surprised no one. Only pity for the top European team. The defeat by France in Moscow rang the first alarm bell, but the message was not received, and the failures continued in Prague and Tel Aviv. The combination of results on the final matchday left the “Bear” in second place in the group and out of the competition for the first time in forty years! The giant with feet of clay collapsed with a deafening noise, but this was bound to happen with mathematical certainty. Basketball, and those who controlled it and made the decisions, either refused or were unable to see that just as the world around them was changing, so too should the sport. When the Lithuanians departed, there had been no preparation for what would follow.

The production of new players had stopped, Gomelsky, who was once considered a pioneer with innovative ideas, had probably rested on his laurels too long and was no longer interested in the progress of Soviet basketball. The “Bear,” because of those who once made it mighty, fell into the deepest hibernation and, in the end, never woke up again. Yet, when it roared and showed its claws, it terrorized European basketball for half a century. Fifty years of triumphs cannot be erased so easily, and whatever happened after the collapse of the USSR, Soviet basketball will always have Munich…